How do you define stainless steel?

Stainless steels are alloys of steel that feature a shiny finish and are highly resistant to corrosion. They are composed of iron with a minimum of 10.5% chromium, along with other alloying elements such as nickel and molybdenum.

When chromium reacts with oxygen, it creates a thin layer of Cr2O3 on the steel’s surface. This layer provides stainless steel with its corrosion resistance by preventing oxygen from reaching the underlying metal. Consequently, it stops rust from penetrating into the material.

Stainless steel comes in over 150 different grades, grouped into five main subcategories.

Austenitic Stainless Steel

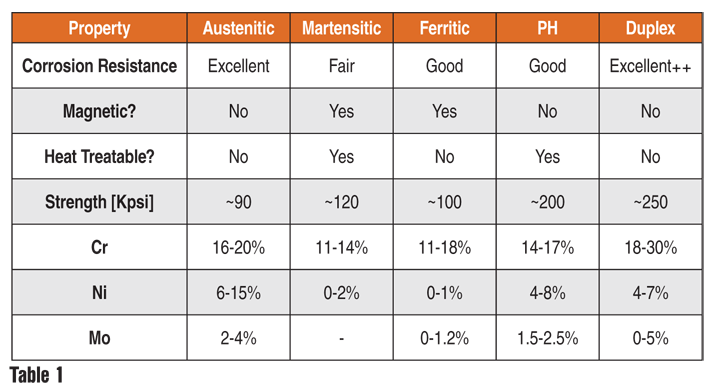

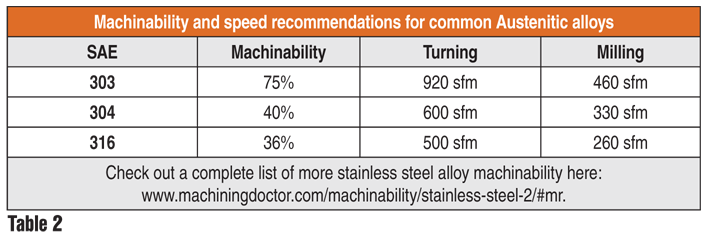

Austenitic stainless steel is the most widely used class of stainless steels. Characterized by a high chromium content of up to 20% and nickel levels reaching 15%, this group is known for its superior resistance to corrosion. The significant nickel content, however, makes these alloys pricy and very challenging to machine. Compared to other stainless steels, austenitic grades generally have lower strength and hardness. Most alloys in this category contain less than 0.1% carbon, which increases ductility and therefore requires careful attention to chip control and built-up edge (BUE). Variants marked with an “L” suffix, such as 304L or 316L, have extremely low carbon content, around 0.03%, and are even more difficult to machine (because of extra ductility). Common machining difficulties include high cutting forces, substantial heat generation and BUE, where the workpiece material adheres to the tool’s cutting edge. Notch wear frequently occurs at the depth-of-cut line, and alloys with increased nickel and molybdenum content exhibit poorer machinability.

Best practice:

- Use TiAlN PVD grades or thin-layer CVD grades.

- Don’t use very low cutting speeds, as built-up-edge forms when there isn’t enough heat at the cutting edge.

- Apply good coolant supply directed to the cutting edge.

- Vary the depth of cut to reduce notch wear risk.

Martensitic Stainless Steel

Martensitic stainless steel is the second most common category of stainless alloys. These alloys feature up to 14% chromium and contain only small amounts of nickel. They can undergo heat treatment and hardening, providing greater strength compared to austenitic alloys. However, their corrosion resistance is limited, making them suitable primarily for use in atmospheric environments.

Ferritic Stainless Steel

Ferritic stainless steel materials contain up to 18% chromium with almost no nickel. They have better corrosion resistance than martensitic grades but less than austenitic ones, and cannot be hardened by heat treatment.

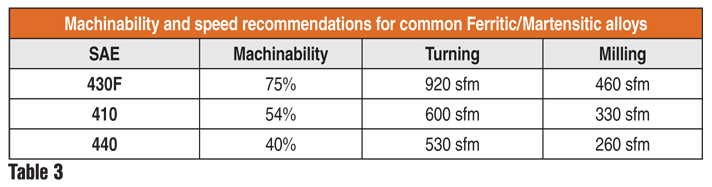

Martensitic/Ferritic stainless falls between regular steel and stainless steel materials. Carbide grades for both alloy steel and stainless steel work well on them. Typical wear includes flank and crater wear (similar to alloy steel), with occasional BUE. The machinability is better compared to austenitic stainless.

Grades with suffix F (such as 430F/420F) are free-cut materials with more sulfur and less molybdenum. This change improves machining ease but reduces corrosion resistance. Grades with suffix C, like 440C, have higher carbon levels, which increases their strength and hardness after heat treatment.

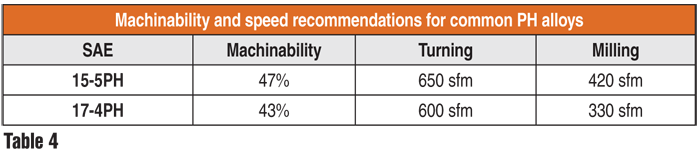

Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel

This group, referred to as PH stainless steels, offers outstanding resistance to corrosion and can be heat-treated to achieve tensile strengths up to three times greater than standard austenitic types. This is accomplished by incorporating elements like copper, aluminum and titanium into their makeup. PH alloys are commonly utilized within aerospace and the oil and gas industry sectors, where both high strength and superior corrosion resistance are essential.

PH stainless steel grades are available in two main conditions: annealed (condition A) and tempered (condition C). The annealed comes in hardness between 20-30 HRC, making it easier to machine. Once machining is complete, parts can be age-hardened to a hardness of 32-42 HRC. Tempered (condition C) alloys come in hardness up to 43 HRC and can be further hardened to exceed 50 HRC. It is important to consider the alloy’s condition and hardness when determining appropriate cutting parameters.

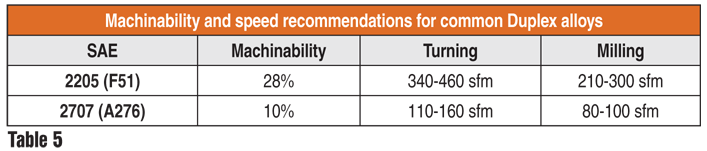

Duplex Stainless Steel

This category is referred to as duplex because these alloys possess a dual-phase structure comprising both austenitic and ferritic phases. As a result, they offer the advantages of both types, including enhanced strength, improved toughness and superior corrosion resistance. Compared to austenitic stainless steels, duplex alloys provide greater resistance to corrosion and higher tensile strength. Their chromium content can be as high as 30%, which is significantly more than that found in austenitic grades. In terms of machining, general guidelines are much like those for austenitic stainless 316, though machinability is roughly 20% lower nd greater emphasis is needed on clamping stability. These steels are generally less costly than austenitic stainless due to their reduced nickel content. However, they are much less widely used, primarily because they are harder to machine and their strength and corrosion resistance decrease at temperatures above 570°F (300°C)

Related Glossary Terms

- alloys

alloys

Substances having metallic properties and being composed of two or more chemical elements of which at least one is a metal.

- built-up edge ( BUE)

built-up edge ( BUE)

1. Permanently damaging a metal by heating to cause either incipient melting or intergranular oxidation. 2. In grinding, getting the workpiece hot enough to cause discoloration or to change the microstructure by tempering or hardening.

- built-up edge ( BUE)2

built-up edge ( BUE)

1. Permanently damaging a metal by heating to cause either incipient melting or intergranular oxidation. 2. In grinding, getting the workpiece hot enough to cause discoloration or to change the microstructure by tempering or hardening.

- chemical vapor deposition ( CVD)

chemical vapor deposition ( CVD)

High-temperature (1,000° C or higher), atmosphere-controlled process in which a chemical reaction is induced for the purpose of depositing a coating 2µm to 12µm thick on a tool’s surface. See coated tools; PVD, physical vapor deposition.

- coolant

coolant

Fluid that reduces temperature buildup at the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Normally takes the form of a liquid such as soluble or chemical mixtures (semisynthetic, synthetic) but can be pressurized air or other gas. Because of water’s ability to absorb great quantities of heat, it is widely used as a coolant and vehicle for various cutting compounds, with the water-to-compound ratio varying with the machining task. See cutting fluid; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.

- corrosion resistance

corrosion resistance

Ability of an alloy or material to withstand rust and corrosion. These are properties fostered by nickel and chromium in alloys such as stainless steel.

- depth of cut

depth of cut

Distance between the bottom of the cut and the uncut surface of the workpiece, measured in a direction at right angles to the machined surface of the workpiece.

- ductility

ductility

Ability of a material to be bent, formed or stretched without rupturing. Measured by elongation or reduction of area in a tensile test or by other means.

- hardening

hardening

Process of increasing the surface hardness of a part. It is accomplished by heating a piece of steel to a temperature within or above its critical range and then cooling (or quenching) it rapidly. In any heat-treatment operation, the rate of heating is important. Heat flows from the exterior to the interior of steel at a definite rate. If the steel is heated too quickly, the outside becomes hotter than the inside and the desired uniform structure cannot be obtained. If a piece is irregular in shape, a slow heating rate is essential to prevent warping and cracking. The heavier the section, the longer the heating time must be to achieve uniform results. Even after the correct temperature has been reached, the piece should be held at the temperature for a sufficient period of time to permit its thickest section to attain a uniform temperature. See workhardening.

- hardness

hardness

Hardness is a measure of the resistance of a material to surface indentation or abrasion. There is no absolute scale for hardness. In order to express hardness quantitatively, each type of test has its own scale, which defines hardness. Indentation hardness obtained through static methods is measured by Brinell, Rockwell, Vickers and Knoop tests. Hardness without indentation is measured by a dynamic method, known as the Scleroscope test.

- machinability

machinability

The relative ease of machining metals and alloys.

- physical vapor deposition ( PVD)

physical vapor deposition ( PVD)

Tool-coating process performed at low temperature (500° C), compared to chemical vapor deposition (1,000° C). Employs electric field to generate necessary heat for depositing coating on a tool’s surface. See CVD, chemical vapor deposition.

- stainless steels

stainless steels

Stainless steels possess high strength, heat resistance, excellent workability and erosion resistance. Four general classes have been developed to cover a range of mechanical and physical properties for particular applications. The four classes are: the austenitic types of the chromium-nickel-manganese 200 series and the chromium-nickel 300 series; the martensitic types of the chromium, hardenable 400 series; the chromium, nonhardenable 400-series ferritic types; and the precipitation-hardening type of chromium-nickel alloys with additional elements that are hardenable by solution treating and aging.

- tensile strength

tensile strength

In tensile testing, the ratio of maximum load to original cross-sectional area. Also called ultimate strength. Compare with yield strength.

- titanium aluminum nitride ( TiAlN)

titanium aluminum nitride ( TiAlN)

Often used as a tool coating. AlTiN indicates the aluminum content is greater than the titanium. See coated tools.