Machine tool builders and distributors are offering to put together complete turnkey manufacturing packages in an effort to win customers.

Wouldn’t it be great to buy a machine tool and wake up one morning to find it installed in your shop, tooled up, and running good parts? That’s the premise behind a marketing trend being adopted by more and more machine tool builders and distributors. They are recasting themselves in the role of what one distributor calls "unpaid consultants," putting together complete commodity turnkey systems that are ready to run from the moment they are installed on the customer’s shop floor. With such value-added service, these vendors hope to rise above their competitors in a market filled with machines that perform with nearly equal speed, precision, and reliability.

Turnkey manufacturing systems are nothing new. Traditionally, however, turnkeys were machines for large-scale operations designed and built from custom parts. An automotive manufacturer’s transfer line is, by definition, a turnkey system. This newer breed of single-machine turnkey systems, offered by companies like Mazak Corp., Florence, KY, and Makino Inc., Mason, OH, is built primarily from commodity machining or turning centers and off-the-shelf components.

Turnkey vendors are building these systems for companies of nearly any size, although the most common customer is a larger manufacturer. "A turnkey is usually for parts that are done in house," says Brian Davis, sales manager for the OEM Group at Sandvik Coromant Co., Fair Lawn, NJ. But smaller manufacturers and even job shops are looking for turnkey services, too. All it takes is one large-volume job, says Davis, and a job-shop owner can feel justified in shopping for turnkey services. For example, one small Canadian company Davis has worked with required a turnkey when it was chosen as a second-tier supplier for an automotive part.

Like the larger transfer lines, these commodity turnkeys are fully equipped, ready-to-run systems. Gary Kyne, Makino’s general manager, production machinery division, says his company’s turnkeys include not only a machine tool but also the fixturing, cutting tools, material-handling equipment, and ergonomic features required to run a part.

The turnkey vendor supplies more than hardware, however. "A turnkey is all of the processes, and all of the cutting parameters that are required to make the part," says Ed Silver, North American OEM sales manager for Kennametal Inc., Latrobe, PA. By the time a customer takes delivery of a turnkey system, the supplier has worked out all of the system’s kinks, bugs, and bottlenecks. The vendor will also have taken into consideration the workflow to and from the machine, making sure all of the workhandling systems are coordinated with the shop’s existing equipment. Companies that need something less than a fully engineered system can benefit from these services as well. "If a customer wants anything from programming to tooling - what we call value-added engineering services - that’s what we call a turnkey," says Kent Lorenz, executive vice president of Ellison Machinery of Wisconsin, a distributor located in Pewaukee, WI.

Even more important than the sale of engineering services, the turnkey vendor is selling its assurance that the system meets whatever criteria the customer has specified. "Usually the customer is after cycle time," says Sandvik’s Brian Davis. Other goals might be a specific level of quality or the longevity of one of the cutting tools used to machine the part. Whatever the customer and the vendor agree to at the beginning of the turnkey project becomes the one criterion that will determine if the machine builder or distributor will make the sale.

"The customer doesn’t have to pay for it until we can deliver a system that meets what we guaranteed," says Kent Lorenz. "I’m proud to say we’ve never failed to do so," he adds. "We’ve always delivered a turnkey that works. But there’s certainly a level of risk there every time."

The vendor also might calculate a cost justification for the system’s purchase based on the proposition that this target criterion will be met. "We’ll come in and show them how, with the productivity or throughput increase, they can justify the new capital investment from a return-on-investment standpoint," says Makino’s Gary Kyne.

To get a turnkey, a shop may work directly through the machine tool builder, or it may work through a local distributor. Tree Machine Tool Co. Inc., Racine, WI, for instance, participates in turnkey projects, but it only works through distributors like Ellison Machinery. Whether it’s a builder or a distributor that creates the turnkey, the end result - a working system installed on the shop’s floor - will be the same, but there may be some differences in the experience and the expertise the vendor brings to the project. The builder, being a larger national or international organization, will have the resources to engineer a project of nearly any scope or sophistication. According to Ellison Machinery’s Kent Lorenz, the distributor may not be able to draw on a base of experience as broad as a machine tool builder’s, but the distributor may be more familiar with the type of work performed by shops in its region. For instance, there are a number of small engine manufacturers in Ellison Machinery’s corner of Wisconsin. As a result, the distributor looks for people with experience in this type of manufacturing when it hires new engineers.

Sometimes the firm designing the turnkey system is neither a builder nor a distributor, according to Kennametal’s Ed Silver. Companies are springing us that only provide the engineering for a turnkey project. These companies can help a machine builder put together a complete package, but they also can put together a system by tooling, fixturing, and programming a shop’s existing equipment.

Profit Motive

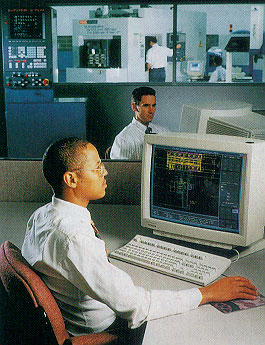

Turnkeys are definitely becoming a hot item, and more and more machine tool builders and distributors are offering them. Kent Lorenz says that at least half of the business Ellison Machinery does is turnkeys. His company just moved into a 16,000 sq.-ft. facility to give its engineers the space to service its turnkey accounts. Mazak, seeing this trend, has opened a National Technology Center at its Florence campus. The center has a number of CAD/CAM stations at the facility that can be linked to machines set up on the center’s demonstration floor. These computers and machines are solely for the purpose of designing and building systems for Mazak’s customers (Figure 1).

The motivation for a shop of any size to purchase a turnkey system is a lack of in-house staff time or expertise. "A manufacturing engineer with a small staff is carrying a higher workload today than he did 5 years ago," says Lorenz. "So if he can off-load that engineering to the supplier and lessen his risk, he’ll do that in a heartbeat."

Both the buyer and the supplier benefit from what Makino’s Gary Kyne calls this "one-stop shopping" approach to buying a manufacturing system. By leaving the engineering to its supplier, the purchasing company can concentrate on production - turning out quality parts quickly and efficiently while maintaining processes at their optimal performance level. The initial development of the system is left to the companies that have much greater experience in engineering machines, tools, and fixtures and in programming those particular components to produce and handle parts.

Figure 1: Engineers in the CAD/CAM department of Mazak’s new National Technology Center perform process-verification routines for their turnkey customers.

The system buyer also benefits from the wide range of experts that come together to design the system. A turnkey typically involves not only the machine builder’s or distributor’s engineers, but also engineers from the component manufacturers (Figure 2). These engineers have seen a wider variety of applications than an engineer working for a single shop might see, and they may be able to draw on this experience to come up with solutions they have seen work with similar applications elsewhere. Gary Kyne says shops that have honed their production skills may not be as aware of innovations in manufacturing system technology as the machine tool vendor’s engineers are.

"It’s really more of a benefit to them to continually upgrade their manufacturing-engineering technology through their suppliers, because we tend to be more exposed to what is the latest available," he says.

Turnkeys are also a way for shops to spread around some of the risks associated with a new application. The buyer doesn’t have to fear going broke as its in-house people engineer and fine-tune a system the company has already bought and paid for. Frequently, a turnkey system is ready to produce a return on the buyer’s investment by the time the buyer is expected to pony up the cash for it. As the system is being put together, the vendor may require some progress payments, but typically, no money changes hands until after the vendor has a completely engineered system on paper. It is at this point that the vendor submits a bid for the system, and the buyer commits to the project. Gary Kyne says Makino may invest up to $20,000 in engineering to develop a turnkey proposal for a customer. And this money might never be recouped if the customer decides to go with another builder that is also investing thousands to design a turnkey system for that customer. Brian Davis says Sandvik will supply tools and components to the machine tool builder for testing well before the customer has inked a deal with the vendor just to get a chance at the business.

Figure 2: During the course of a turnkey project, the turnkey vendor and the component suppliers may meet several times to discuss the engineering required to achieve the project's goals.

Why would a seller want to put up this much money and time without a firm commitment from a customer? Primarily because it has to. Most machine tool manufacturers acknowledge that their competitors are making machines as capable of producing good parts as theirs. With so many sellers in the market trying to sell similar machines, the competition has become fierce, says Gary Kyne, and each company has tried to top the other in speed or features. "We’ve elected not to compete in the arena of mine’s bigger, stronger, faster, and cheaper, because that’s real dog-eat-dog," he says. "We’d rather be in the business of selling process solutions to our customer, so we currently employ probably the largest application engineering staff of any commodity-machine builder in the United States."

Toolmakers see their participation in turnkeys as a wise marketing strategy as well. A customer that has bought a completely engineered system will be reluctant to try anything new or different once the system is up and running, says Kennametal’s Ed Silver. This gives the lucky tool manufacturer whose products are chosen for a turnkey a near lock on the business for the entire run of parts. "If you lose out at the machine-tool-builder level, you may be looking through the window for another 2 years before you can get to test your carbide on the machine," he says.

Getting Started

A shop in the market for a turnkey system must be ready with a part print, and it should know what machine or machines it will need to make the part. Then, the shop’s engineers must decide at what level of performance the equipment must operate to produce the part at a profit. This is the starting point that will guide the shop to the right supplier and give that supplier a target it can aim at with its quote. From this point, the shop’s engineers must be ready to supply whatever additional information the seller asks for.

The seller will look at the part print to determine what tools and part-handling systems will be needed. Gary Kyne says it’s useful for the vendor to have a prototype part or a model to work with as well. "This helps our engineers conceptualize the fixtures a little more quickly," he says. The part data will also be analyzed to determine the optimal machining parameters. Kent Lorenz says Ellison Machinery will do a formal time study listing all the speeds and feeds and times for changing pallets, indexing turrets, and any other task involved to show the customer how a target cycle time might be achieved.

Typically, the seller’s information-gathering will bring its engineers to the customer’s shop floor at some point in the process. At Ellison Machinery, according to Lorenz, a shop visit is a regular part of his company’s selling strategy. "If a customer calls us requesting literature on a specific machine or a machine of a specific size, one of our sales engineers goes out to meet with him immediately," he says. National companies with regional sales forces may get some of their information about the customer from field representatives, who may already be working with the company. In some cases, according to Lorenz, even the customer’s customer will be invited to sit down with the vendor’s engineers and the customer to determine what the job’s requirements will be and to discuss the processes and cycle times that the system will use.

Through its shop visits, interviews with the customer, and discussions with field salespeople, the vendor will try to get a feel for the customer’s level of technology and standard practices. The part print and part information will tell the vendor what components will be needed, but it is this additional information that will help the vendor integrate the system into the shop’s current operations. Gary Kyne says Makino will want some information on the customer’s budget constraints up front to avoid investing engineering time in a system the customer can’t afford. The machine tool builder also looks at the shop’s layout and the utilities available at the site where the machine tool will be installed. Makino’s engineers also want information about the other machines upstream and downstream to plan workflow to and from the new machine.

Kent Lorenz lists a number of issues his engineers explore with the customer before a turnkey is planned. Among these issues are:

- How the customer handles inventory.

- What types of machines are currently in use at the shop.

- How the machines are programmed. Whether or not programs are written offline and dumped into the machines through a network. What procedures must be followed to update programs.

- Whether or not the shop is ISO certified, and if so, what protocol and procedures it follows.

- Whether or not the shop uses tools preset in the toolcrib.

- Whether or not each machine has tooling dedicated to it.

- Whether or not the shop uses a central coolant system.

- How the shop disposes of its chips.

- Whether each machine is used to perform several operations or used for only specific operations.

- What types of part volumes the shop runs.

- What types of work the shop’s typical customers perform and what the delivery and quality requirements of those industries are.

Some customers may get nervous divulging so much about their businesses or allowing a vendor’s personnel to go exploring on their shop floor. "There are times we never get past the lobby," says Kent Lorenz. But such fears are unfounded, even if a shop should discover that its supplier is working for a competitor at the same time, which Lorenz says has happened. "If we were to share some information from one customer with another, we’d probably never do business with either one in the future," he says. Suppliers will sign nondisclosure agreements if asked, and will go out of their way to maintain confidentiality. Gary Kyne says Makino will go so far as to set up enclosures on its shop floor to maintain its customers’ confidentiality requirements.

Team Building

Once this information is gathered, the machine tool builder or distributor begins to put together the team that will design and build the system. It is at this point that the turnkey vendor’s engineers decide whose tooling will go on the machine.

"Half the time, the customer has a preference, and they tell the vendor who they want to use," says Sandvik’s Brian Davis. "The rest of the time, if the vendor is allowed to dictate, they will use who they feel most comfortable with." Often, according to Kennametal’s Ed Silver, the customer will give the turnkey vendor a selection of three to five acceptable tooling companies ranked by preference, and the vendor is allowed to choose. While the machine tool builder or distributor may have tooling suppliers its engineers are comfortable working with, it also wants to maintain any working relationships the customer may have built up with its own suppliers.

However, according to Silver, there have been times when the turnkey vendor has overruled the customer’s choice of tooling supplier. With the ultimate responsibility for the success of the project resting on the turnkey vendor’s shoulders, the turnkey vendor’s engineers may be reluctant to use a tooling supplier that has disappointed them in the past. Typically, the customer defers to the turnkey vendor’s experience, knowing that if the vendor fails to meet the requirements of the project, the customer may be blamed for its insistence on using the wrong supplier.

Often, what distinguishes one machine tool builder’s or distributor’s turnkey from another is its selection of tools, fixtures, and workhandling equipment. Ellison Machinery’s Kent Lorenz says that most machines in the same class have similar performance characteristics, so the choice of machine tool vendor will make little difference. What may make or break a turnkey, he says, is the vendor’s willingness to ferret out unique components that will improve cycle times, quality, or tool life.

If given a choice, the turnkey vendor’s engineers will choose component suppliers they know are willing to participate in the planning and experimentation phases of the project. These suppliers keep the engineers updated with innovations, and they freely supply the machine tool builder or distributor with components for test cuts. Ed Silver says that most turnkey vendors will pick a larger toolmaker, because the bigger companies have the financial resources and engineering expertise to contribute to the project’s preliminary stages and will have product lines broad enough to have the precise tools needed for the project. Like the automakers they work with, machine tool builders may create a tiered hierarchy for their suppliers, according to Silver. They make a large tool company such as Kennametal or Sandvik their tier-one supplier. It then becomes the tier-one toolmaker’s responsibility to find and purchase any tools it can’t supply itself.

To meet the turnkey vendor’s needs, companies like Kennametal and Sandvik have established OEM divisions. Salespeople in these divisions consider the machine tool builder or distributor their customer, according to Ed Silver. "The representative that calls on a particular machine tool builder becomes familiar with that line," he says. "He knows the machines and he knows their capabilities."

In some cases, a tooling vendor will enter into in a formal partnership with a machine tool vendor to design special tools. It’s rare for such a relationship to be formed to supply special tools to a turnkey account, however. Kent Lorenz says, "We try to work with as much off-the-shelf as we can, because once customers get their systems running, they’re going to want to purchase replacement components. And the more off-the-shelf we can be, the easier and less expensive it is for them in the long run to maintain that system." Sometimes, especially in the case of workholding, the components will have to be custom designed. Lorenz says about half of Ellison Machinery’s turnkey projects involve workholding custom-designed by a local supplier.

Once a turnkey vendor has chosen a supplier, the supplier’s technical staff is immediately enlisted to work on the project team. These experts are called on to select tools and tool materials, design fixtures, determine machining parameters, and offer advise on the best machine to use with their components. Often, this counsel is used by the turnkey vendor to develop its quote well before the customer has formally chosen the vendor to build its turnkey. Much of this work is done in face-to-face meetings with the turnkey vendor’s engineers at the vendor’s facility or with the customer’s personnel at the shop.

"Sandvik’s OEM group gets involved at both ends right away," says Brian Davis. "We work with the builder, and we get the salesman who calls on that customer involved."

Guaranteed Satisfaction

After the turnkey vendor and the suppliers have the system on paper, they are ready to submit a quote to the customer with all of the plans and components spelled out and a schedule outlined for the completion of the project. The quote will also include the turnkey vendor’s performance guarantee. This is the key requirement the customer has said is essential for the application’s success. Nothing will be shipped to the customer until this level of performance has been met.

The turnkey is originally built at the machine tool builder’s or distributor’s facility. During the experimental or trial phase of the project, the turnkey vendor may use equipment already installed at its facility. Ultimately, a system made up of the customer’s components will be built on the turnkey vendor’s floor. Before the vendor is ready to call in the customer for its final OK, the vendor will run the customer’s parts on the system and work out all the bugs. Once the turnkey is producing good parts, the customer is invited to the facility for the final runoff.

"Generally the amount of parts demonstrated can run anywhere from 30 to 35 parts up to several hundred," says Makino’s Gary Kyne. The actual number of the sample will depend on the customer’s statistical-process-control acceptance requirements. Ellison Machinery’s Kent Lorenz says some customers may require a run of hundreds of parts as well as a full statistical analysis of the quality of the parts produced. This type of sophisticated verification is more common for large dedicated systems, however. Commodity-machine customers typically look more for a first-good-part type of process verification.

It’s possible even at this late stage for the customer to refuse delivery of the system because it doesn’t meet the performance requirements, but such an occurrence is rare. Typically, the customer will have been consulted regularly during the progress of the project and will know what to expect at the runoff. Sometimes the vendor may ask for money up front - in the form of a down payment or progress payments - that the shop will lose if the system is not installed. But there are cases when the customer loses the contract, or the part program is canceled, before the system is up and running in the customer’s shop. And in many of these cases, it is the turnkey vendor and its suppliers that stand to lose the most.

"We may invest up to $20,000 in time and energy preparing a proposal and not get the order, either because we lose the business to a competitor or the program gets canceled," says Gary Kyne. "That’s just one of the costs of doing business."

The time the turnkey vendor invests in planning and building a working system will vary with the complexity of the project. Gary Kyne says Makino may need 4 to 5 months for a horizontal machining center to produce two different parts using 15 tools. A project that requires a high degree of automation, on the other hand, may take 12 to 14 months from the initial discussion with the customer to the installation of the system on the customer’s shop floor. Ellison Machinery takes 4 to 6 weeks to develop a system, according to Kent Lorenz. Most of that time is spent simply waiting for the machine and tooling to be delivered. Once the system arrives at Ellison Machinery’s facility, it takes about a week for the engineers to get it up and running.

On the Floor

The turnkey vendor’s services don’t always stop with the installation of the system. Kent Lorenz says Ellison Machinery provides training as long as the customer owns the equipment. The machine tool builders and tooling suppliers offer training as well. Most turnkey vendors say they try to stay in touch with their customers to make sure the system is performing as well as it was designed to perform.

"Once we complete a runoff here at our facility, we duplicate it on the customer’s floor just to verify that everything is right, the machine is level, and nothing has broken during shipment," says Kent Lorenz. "Then we follow up in 90 days with an on-site visit just to make sure everything’s OK. I would say during that first year, we probably have four to 10 follow-up visits with a customer."

The machine tool vendor probably won’t get involved in routine maintenance, however. For new tools and other replacement components, the customer will typically go through the component maker’s standard distribution channels, either field salespeople or a local distributor. Makino does offer tool-management services for a fee to its turnkey-system customers. "We take care of the specifications, the tool drawings, the procurement, the follow-up, the packaging, the tryout, and the redelivery back to our customer," Makino’s Gary Kyne reports.

Shops should realize that by purchasing a turnkey system, they may no longer be able to claim their processes as exclusively theirs. Unless a customer specifies and is willing to pay for a proprietary system, the vendor will feel free to use the same components and configurations on another customer’s system, even if that customer is a competitor. A turnkey vendor that specializes in serving the automotive industry, for instance, may develop a package for one customer to machine bearing races that require a unique workholding system. If another customer wants a system for the same type of part, it is to the vendor’s and that customer’s benefit for the vendor to use components he knows will work because they have been proven on other projects.

"The only time customers get concerned about the propriety of a process is if we are integrating a very specific cutting tool solution that’s either their trade secret or is covered by some kind of patent," says Gary Kyne. "Usually they want protection on their new-product introduction."

For shops in the market for a new machine tool, the engineering challenges may seem daunting. And banking on the new equipment’s higher performance to pay for the investment may look like a crapshoot. But with the purchase of a turnkey system, these worries and risks can be spread around. The shop receives the benefits of working with engineers who specialize in designing systems, and the vendors are able to distinguish themselves from their competitors with value-added services.

Related Glossary Terms

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- coolant

coolant

Fluid that reduces temperature buildup at the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Normally takes the form of a liquid such as soluble or chemical mixtures (semisynthetic, synthetic) but can be pressurized air or other gas. Because of water’s ability to absorb great quantities of heat, it is widely used as a coolant and vehicle for various cutting compounds, with the water-to-compound ratio varying with the machining task. See cutting fluid; semisynthetic cutting fluid; soluble-oil cutting fluid; synthetic cutting fluid.

- machining center

machining center

CNC machine tool capable of drilling, reaming, tapping, milling and boring. Normally comes with an automatic toolchanger. See automatic toolchanger.

- payload ( workload)

payload ( workload)

Maximum load that the robot can handle safely.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.