Richard Kegg might not be a household name, but you likely are quite familiar with his 1952 invention: the CNC milling machine.

You probably can’t imagine running your CNC machine shop on manual mills and lathes that count on people for everything. How long could you compete? How long could you remain in business? Yet for over 30 years, people couldn’t imagine using CNC machines.

What was the resistance in adopting CNCs? It was the same resistance seen today regarding robots for CNC machine tending. Does the following sound familiar?

- “It’s too complicated.”

- “I’ve never done that before.”

- “I’ve always done it this way; I don’t want to change.”

- “What if it doesn’t work — then what?”

- “What will people think?”

Times, minds and ideas change. We hear these legitimate statements and questions today about CNC machine-tending robots. Are there legitimate responses and answers? Absolutely. In some ways, this is not surprising since we are about 15 years into what could be a 30-year acceptance cycle.

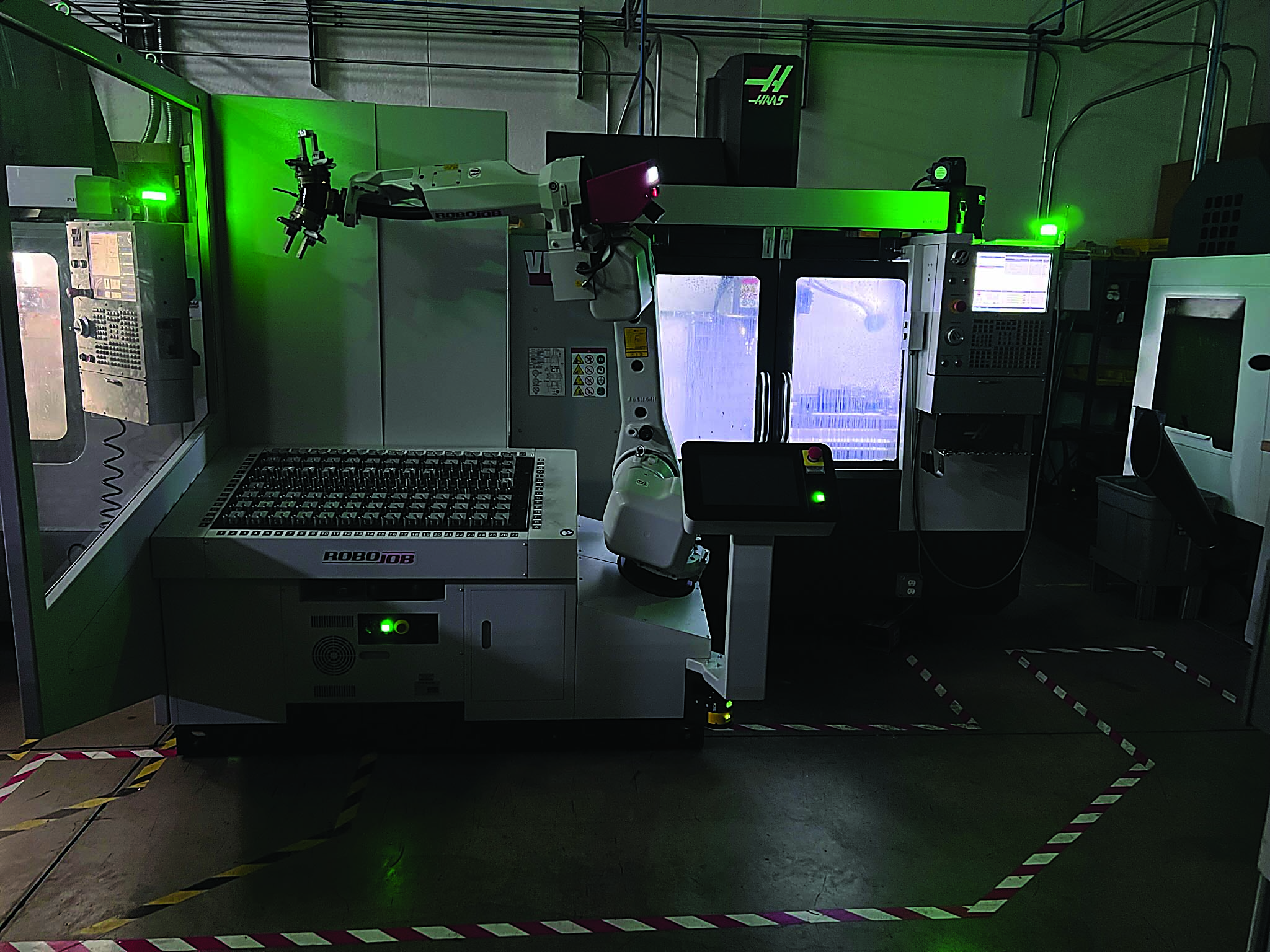

Sixteen years ago, a Belgian machine shop needed a way to compete on the global stage. The business was tired of losing to companies in low-wage countries and knew that it needed CNC automation to regain what had been lost. But no one made a standard robotic solution for CNC machines. So the shop engineered and built a solution for itself, which started the CNC robotic industry and the company RoboJob NV.

Purpose-built, CNC machine-tending robotic systems are catching on faster than the CNC machine ever did. When the CNC machine was invented, the ATM did not exist for another 15 years. In the beginning, even ATMs were questioned because people didn’t trust them. People were accustomed to talking with a person to deposit and withdraw money because the human touch mattered.

Although machine shop leaders appreciate machine-tending robots for the problems they solve, another group appreciates them even more: serious machinists. We’ve heard machinists talk about their days before robots. They often would work on two CNCs simultaneously — setting up one CNC while the other ran parts. When machinists heard the cycle end alarm, they would stop setting up their next job, walk over to the other CNC, unload and reload it and then go back to the setup, which hindered productivity. Programming CNC machines requires a lot of focus, and disrupting your attention span can lead to costly programming errors.

Ask machinists who have worked with robotic machine tending, and they will tell you they are better at their craft and make fewer errors because a robot is tending the CNC so they can focus on the high-value cerebral work they love. No serious machinist loves loading and unloading a CNC machine. If one does, he or she doesn’t love it for long.

To view a video of this robotic automation visit: https://qr.ctemag.com/1f344

Contact Details

Related Glossary Terms

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- milling machine ( mill)

milling machine ( mill)

Runs endmills and arbor-mounted milling cutters. Features include a head with a spindle that drives the cutters; a column, knee and table that provide motion in the three Cartesian axes; and a base that supports the components and houses the cutting-fluid pump and reservoir. The work is mounted on the table and fed into the rotating cutter or endmill to accomplish the milling steps; vertical milling machines also feed endmills into the work by means of a spindle-mounted quill. Models range from small manual machines to big bed-type and duplex mills. All take one of three basic forms: vertical, horizontal or convertible horizontal/vertical. Vertical machines may be knee-type (the table is mounted on a knee that can be elevated) or bed-type (the table is securely supported and only moves horizontally). In general, horizontal machines are bigger and more powerful, while vertical machines are lighter but more versatile and easier to set up and operate.