I once thought nothing of boring a new set of top jaws. Just remove half a dozen cap screws, take the old jaws out, bolt on fresh jaws, attach a spider or boring ring and crank the hand wheel until the part fits. Setups were long in the 1980s and my boss considered 2 or 3 hours of downtime each day a normal cost of business.

Today, shops might opt for a quick-change chuck. Simply twist a few screws and load a new set of top jaws. And, compared to the hours of lost production in the prehistoric days of paper tape and brazed carbide cutting tools, dropping eight to 10 grand for a quick-change chuck is a no-brainer.

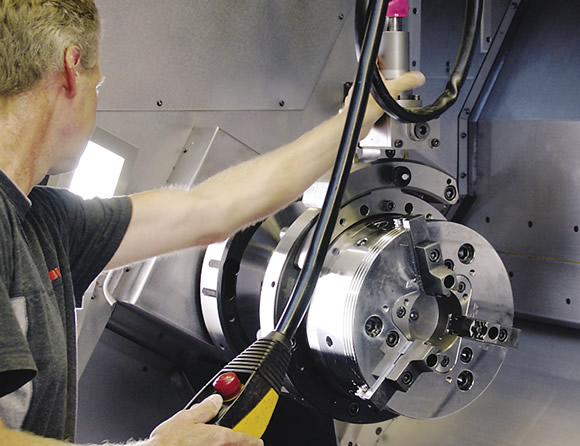

Swapping a Centrotex chuck takes under a minute, and is guaranteed to 5µm runout and repeatability, according to Hainbuch America.

Exploded view of Hainbuch’s TOPlus collet system together with a Centrotex masterplate.

But because of different workholding requirements, sometimes even a quick-change chuck can’t cut the mustard. Collet chucks, faceplates and expanding mandrels are just some of the other workholders found in most turning departments, and swapping one out means muscling 20 lbs. or more of an uncooperative steel chuck out of a CNC lathe before mounting whatever workholding device stands at bat next. This is a something that even the speediest setup man needs 20 minutes to accomplish.

“Our industry has worked extremely hard over the last 20 to 30 years to take minutes or even seconds out of cycle time. What we didn’t do is figure out how to take minutes and hours out of changeover time,” said Jeff Estes, director of Partners in THINC Technology Centers for machine tool builder Okuma America Corp., Charlotte, N.C.

Because customers demand products with short lead times and single-digit lot sizes, the time it takes to set up a machine frequently exceeds the time needed to machine the parts. Estes said: “For a lot of our customers, their first part is their only part. They are making extremely difficult, challenging parts. Production output is always going to be based on the weakest link in your system, and that is typically the setup.”

Hainbuch America Corp., Germantown, Wis., addresses this weakest link with its Centrotex quick-change workholder. Guri Singh, Hainbuch’s CNC production manager, said: “Centrotex is a way to quickly change the entire chuck, rather than just the jaws themselves. It works off a pair of male and female tapers separated by precision ball bearings. Similar to the way a Sandvik Coromant Capto system works, everything is manufactured in such a way that the deformation of those three components is very precisely controlled, giving you extremely rigid clamping together with accuracy. It’s a mechanism difficult to manufacture but very simple and robust to use.”

For shops looking to reduce setup times, Singh outlined some elements of an effective workholding system. The first is R and R. No, this doesn’t mean a 3-day weekend at the lake. “Runout and repeatability are critical,” he said. “We like to see 5µm or better for both, measured radially as well as axially.”

With this accuracy, Singh said shops can avoid “dialing in” the chuck after mounting or taking a skim cut to true up the jaws. “You should be able to slap it on, tighten it down and go.”

Another important feature in a quick-change chuck is interoperability. Switching from one brand’s 3-jaw chuck to its collet chuck in a minute flat is swell, but switching from brand A’s 3-jaw chuck to brand B’s collet chuck to brand C’s expanding mandrel is better than chocolate cake on your birthday. “In a Centrotex environment, each machine is equipped with a permanent master plate,” Singh said. “Each workholding device you wish to quick-change among those machines is then adapted to that master via a matching plate.”

Flexibility like this means shops can use their existing workholding on any machine in the shop, within reason. “You need a system that will let you grip a part on your 2-axis lathe, then move that same part together with the workholding to a 3-axis machining center with little or no repositioning error or compromised rigidity,” Singh said.

This last point is what separates the men from the boys in the world of quick-change. If you’re looking to keep your CNC moneymakers turning, make fixtures offline. “One of the big markets for a quick-change system such as the Centrotex is in shops with multifunction machines,” Singh said. “You don’t want to take a Mori-Seiki NT or an Okuma Multus offline to bore a set of chuck jaws. That’s why it’s important to buy a quick-change system that lets you prepare workholding on a less expensive machine, an engine lathe, for example, then bring it to the production floor when you’re ready to changeover.”

Singh said shops throw a lot of money at new machines but almost none toward workholding. “Workholding is a boring topic. You go to a tool show and the CNCs are the most entertaining things there. Machine builders do a good job of promoting their speed and accuracy, tool capacity, power, what have you, and customers eat that stuff up.”

While U.S. manufacturing is now dominated by low-volume, high-value products made of difficult materials, about 70 to 80 percent of customers do all turning operations on the standard 3-jaw chuck that came “free” with the machine, according to Singh.

That leaves a lot of room for improvement. When you switch to the optimal clamping device for a given operation, you’ll see a noticeable improvement in cutting performance, tool life and surface finish. A quick-change workholding system takes the pain out of switching to the ideal device at will. Less downtime, higher cutting data, longer tool life, better part quality. These are all upsides that dramatically affect return on machine tool investment.

Being competitive means paying attention to boring details. Get a modular, quick-change workholding system. Your bottom line will thank you. CTE

About the Author: Kip Hanson is a contributing editor for CTE. Contact him at (520) 548-7328 or [email protected].Related Glossary Terms

- boring

boring

Enlarging a hole that already has been drilled or cored. Generally, it is an operation of truing the previously drilled hole with a single-point, lathe-type tool. Boring is essentially internal turning, in that usually a single-point cutting tool forms the internal shape. Some tools are available with two cutting edges to balance cutting forces.

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- chuck

chuck

Workholding device that affixes to a mill, lathe or drill-press spindle. It holds a tool or workpiece by one end, allowing it to be rotated. May also be fitted to the machine table to hold a workpiece. Two or more adjustable jaws actually hold the tool or part. May be actuated manually, pneumatically, hydraulically or electrically. See collet.

- collet

collet

Flexible-sided device that secures a tool or workpiece. Similar in function to a chuck, but can accommodate only a narrow size range. Typically provides greater gripping force and precision than a chuck. See chuck.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- flat ( screw flat)

flat ( screw flat)

Flat surface machined into the shank of a cutting tool for enhanced holding of the tool.

- lathe

lathe

Turning machine capable of sawing, milling, grinding, gear-cutting, drilling, reaming, boring, threading, facing, chamfering, grooving, knurling, spinning, parting, necking, taper-cutting, and cam- and eccentric-cutting, as well as step- and straight-turning. Comes in a variety of forms, ranging from manual to semiautomatic to fully automatic, with major types being engine lathes, turning and contouring lathes, turret lathes and numerical-control lathes. The engine lathe consists of a headstock and spindle, tailstock, bed, carriage (complete with apron) and cross slides. Features include gear- (speed) and feed-selector levers, toolpost, compound rest, lead screw and reversing lead screw, threading dial and rapid-traverse lever. Special lathe types include through-the-spindle, camshaft and crankshaft, brake drum and rotor, spinning and gun-barrel machines. Toolroom and bench lathes are used for precision work; the former for tool-and-die work and similar tasks, the latter for small workpieces (instruments, watches), normally without a power feed. Models are typically designated according to their “swing,” or the largest-diameter workpiece that can be rotated; bed length, or the distance between centers; and horsepower generated. See turning machine.

- machining center

machining center

CNC machine tool capable of drilling, reaming, tapping, milling and boring. Normally comes with an automatic toolchanger. See automatic toolchanger.

- mandrel

mandrel

Workholder for turning that fits inside hollow workpieces. Types available include expanding, pin and threaded.

- multifunction machines ( multitasking machines)

multifunction machines ( multitasking machines)

Machines and machining/turning centers capable of performing a variety of tasks, including milling, drilling, grinding boring, turning and cutoff, usually in just one setup.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.