CNC machining takes a blend of computer skills and machining skills. Some competent machinists, especially old-timers, lack the computer skills needed to go from print to part using CNC machines. I previously lacked the computer skills, but couldn’t tolerate not having complete control of the jobs I was running. Therefore, I taught myself the computer side of CNC machining so I could create my own programs.

My approach to learning was inspired about 20 years ago by my then-12-year-old daughter. I was reluctant to have anything to do with computers, but Joanna was already having great fun and was doing what seemed like complex tasks with ours at home.

One day I asked if she would teach me word processing. After she had me click on the Microsoft Word icon, I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach, envisioning a myriad of complex menus and computer lingo that would take me a decade or so to master.

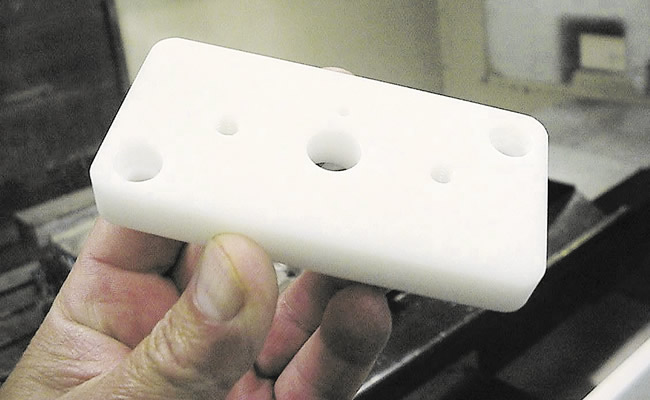

This adapter plate is a simple part, but once you can make one using a CAD/CAM system, you’ll have a good foundation for producing more complex parts. Image courtesy J. Harvey.

I reluctantly asked what to do next. Her answer just about floored me—“Just start typing.” That day taught me two things about computers: While you need an interest in learning, sometimes you must “just do it.”

And even if you can’t work at blinding speeds, that may actually be an advantage. You’ll compensate by focusing on details and by methodically checking your work.

My daughter, by the way, couldn’t stand to watch me slog along with a computer. I believe it’s a generational thing. Still, with all her innate computer ability, she may be the last person I’d trust to engrave expensive mold cavities.

Because I’m not too swift at learning software, I tend to stick with an application once I learn it. I’m reasonably comfortable using our current CAD/CAM system, which is SolidWorks on the modeling side and Camworks on the machining side. I prefer doing all phases of a project, from modeling parts on the computer to planning, programming and machining. Taking ownership of a project vastly cuts down on communication errors and rework. When I can, I like being involved with design as well.

People have different ways they like to learn. Some prefer going to school, and some prefer learning via tutorials. I started to learn CAD by going through a simple tutorial in SolidWorks. I was fortunate to have a seasoned SolidWorks mentor to fall back on when I got stuck. After I completed the first tutorial and modeled a simple part, my mentor said, “Now you know you can do it. From here on out it’s endless.”

Because I’m primarily a machinist who needs to get things done, I tend not to stray too far off the beaten path with unorthodox ways of programming and machining. I try to keep things simple, focusing on what I need to know to get a good product in a reasonable amount of time.

After completing that first tutorial, I switched to my preferred method of learning—having a project to accomplish. The project doesn’t have to be complicated, just useful in some way. By having a project to accomplish, I immediately start to weed out the unnecessary from the necessary.

The “project” approach has downsides, though. It is easy to develop bad habits. I could have avoided many bad habits if I had the patience to take classes or go through more tutorials.

One of the beauties of SolidWorks is you don’t have to be a guru to put it to good use in a machine shop. One hurdle our shop faces is interpreting lousy hand sketches submitted by maintenance mechanics and other customers. At my suggestion, some of the more ambitious customers have learned to model parts using SolidWorks. This approach makes my job as a machinist easier.

The downside is that we now have maintenance mechanics “gone wild.” Some are modeling and inventing all kinds of fancy wrenches, brackets and other parts. One guy came in with a wrench he modeled that had tapered and lofted surfaces. He filleted and radiused nearly everything. Like many people do, apparently he thought that the only thing a machinist has to do is press a few buttons and out pops the part.

I directed him to get rid of that ridiculous model and remodel it using a simple 2D profile. For the angle, I suggested he clamp the wrench in a vise, then whack it with a hammer a few times. Afterward, we heat-treated the wrench. The customer is happy and will be leery of over-engineering anything for a while.

Related Glossary Terms

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- computer-aided design ( CAD)

computer-aided design ( CAD)

Product-design functions performed with the help of computers and special software.