Not that we needed to be reminded, but last month’s news of the tariffs the U.S. announced on imports from all countries makes it painfully obvious that manufacturing in this country remains sorely misunderstood by the general public. And, that goes for much of the news media as well.

In the immediate aftermath of the announcement April 2, most news media outlets framed the tariffs as a political or economic tactic related to inflation or geopolitical motives. While true enough, generally speaking, such coverage gives short shrift to a complex story. A few business-oriented outlets, like Bloomberg and The Wall Street Journal, thankfully made the effort to delve into the stated goal of the tariffs — to spark a renaissance in U.S. manufacturing. Or, in less poetic terms, the goal is to encourage more manufacturers to locate jobs and facilities in this country, something widely known today as manufacturing reshoring.

The tariff news coverage not only underscores the need to update the public’s perception of manufacturing, it pretty much establishes that need as a prerequisite for the success of workforce development and manufacturing reshoring efforts. To explore why, I turned to three industry leaders uniquely qualified and actively leading the charge for the changes needed to improve workforce development and manufacturing reshoring efforts in this country.

|

Harry Moser, a 58- year industry veteran and founder of the Reshoring Initiative, grew up during an era when the U.S. still reigned as the world’s industrial leader and his father and grandfather both worked at the Singer Sewing Machine Manufacturing Co. in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Moser himself spent summer vacations from school working at the plant, which is historically regarded as a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. By the time the plant closed in 1982, Moser was well on his way to forging his own manufacturing career. In 1985, he went to work for Charmilles Technologies, an EDM machine tool company in Lincolnshire, Illinois, where he served as president for nearly 25 years. By the time he retired from the company — now known as GF Machining Solutions — in 2007, Moser had grown tired of watching a long list of American manufacturing plants move offshore. So, in 2010, he founded the Reshoring Initiative to help bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. by providing free analytical tools, such as its Total Cost of Ownership Estimator. The tool helps American companies understand all the financial ramifications associated with offshoring, such as inventory carrying costs, travel costs to check on suppliers, opportunity costs from product pipelines being too long, and risks to intellectual property.

|

Terry Iverson, a 45-year machine tool veteran, is the former owner and president of Iverson & Company, a machine tool sales, service and remanufacturing company in Des Plaines, Illinois, founded by his grandfather in 1931. Since selling the business in June 2023, Iverson has turned his focus to giving back to the industry that has been part of his family for three generations. Iverson, who first began speaking to high school students about manufacturing in the mid 1990s at Moser’s encouragement, founded CHAMPION Now! in 2012 as a nonprofit organization focused on changing the public’s outdated view of manufacturing careers. He’s written two books supporting that mission: Finding America’s Greatest Champion, published in 2018, and Inspiring Champions in Advanced Manufacturing, published in 2023. In addition, Iverson developed and launched Camp CHAMP, a traveling workshop that features two tabletop CNC machines — a mill and a lathe — and a curriculum designed to introduce middle school students to careers in manufacturing. Having received positive feedback from a dozen camps held throughout the Chicago metropolitan area in the past year, Iverson hopes to expand Camp CHAMP workshops nationwide.

|

Roy Sweatman, a 60-year industry veteran, is the president and owner of Southern Manufacturing Technologies Inc. (SMT), an AS9100- and ISO9001-registered precision machine shop in Tampa, Florida, that specializes in complex precision machined components and assemblies for the aircraft, aerospace, defense and medical industries. Sweatman began his career as an apprentice machinist at General Electric in Erie, Pennsylvania. He spent 13 years with GE, working his way up to general manager of GE’s Cleveland, Ohio, facility. He left GE and spent the next five years as general manager for a Cleveland- area precision machine shop. Then, in 1983, he moved to Tampa, Florida, to purchase a small machining company with five employees. That company was SMT, which now employs more than 100 people. Sweatman’s industry involvement, however, goes even deeper than that. In addition to being a CHAMPION Now! board member, Sweatman serves or has served on the boards for a lengthy list of manufacturing trade associations, including the National Tooling and Machining Association (NTMA), the National Institute for Metalcutting Skills (NIMS), the Bay Area Manufacturers Association (BAMA), and Florida’s State Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) known as FloridaMakes. He’s also active with numerous advisory councils for a variety of educational institutions in the Tampa area.

Opportunity knocking

The debate surrounding the government’s tariff strategy has thrust the U.S. manufacturing industry onto the world stage, front and center. As an industry, we must seize this rare opportunity to introduce this nation to an industry that is clean, safe and brimming with well-paying career opportunities to program and operate the most innovative, technologically advanced machines and processes available today. Plus, we must make abundantly clear the strength of U.S. manufacturing and its place in today’s economy.

Take a minute to consider how prolonged access to this media spotlight is an opportunity for the industry to shatter the public’s negative views of manufacturing. Given that the tariffs are intended to spark a manufacturing renaissance, there’s a real possibility the public’s focus on the industry will linger — despite the 90-day tariff pause announced a week later.

Notably ignored by much of the ensuing tariff analysis was any mention of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the vulnerability of extended global supply chains, especially those heavily reliant on single-source suppliers — many of which are in China or Southeast Asia. Plus, labor shortages compounded supply chain bottlenecks during the pandemic due to worker absenteeism, illness and burnout.

While automation, upskilling and workforce retention are now priorities throughout the industry, the skilled labor shortage remains a major hurdle. And, there’s no quick fix for a problem decades in the making.

The once-thriving American middle class, long anchored by a strong manufacturing base, bore the economic brunt of offshoring. Little wonder why the public may still hold a dim view of manufacturing career prospects. Exasperating the labor shortage, meanwhile, has been a 50-plus year crusade in this country pushing everyone to seek higher education.

For a successful renaissance, Moser observed, manufacturing output would have to increase by 30% or more, and that’s not possible unless the federal government and the industry work together to first resolve the skilled labor shortage.

No longer the global leader

The public’s perception that manufacturing is an industry in decline became more entrenched in 2010, which is when China overtook the U.S. as the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. Until that point, the U.S. had reigned as the global manufacturing leader for decades while China struggled with wars, unrest, weak government, natural disasters and poor economic policies. China began turning things around when it implemented economic reforms in the late 1970s, and over the next 30 years transformed into the world’s largest manufacturing hub, according to a 2007 research paper by Angus Maddison titled, “The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, 1960-2030.”

As of 2023, China’s share of global manufacturing reached 31.8% — more than double the 15% global share produced by the U.S., according to the 2024 edition of the International Yearbook of Industrial Statistics published by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. For some perspective on China’s rapid industrial rise, its share of global manufacturing output stood at just 3% in 1990.

![U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Value Added by Industry: Manufacturing as a Percentage of GDP [VAPGDPMA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/VAPGDPMA, April 2, 2025.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/FRED-Chart.png)

Yet, U.S. manufacturing remains strong. As of 2024, the U.S. manufacturing sector added $2.94 trillion to the economy, accounting for 10% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Again, for perspective, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) has compared the U.S. manufacturing output alone against the total GDP of other countries to see where it would rank. This year, U.S. manufacturing would be ranked as the eighth largest economy in the world.

After China and the U.S., the top 10 list of countries with the largest share of global manufacturing output in 2023 includes Japan with 6.6%, Germany with 4.6%, India with 3.2%, the Republic of Korea with 3.0%, the United Kingdom with 1.9%, Italy with 1.8%, Mexico with 1.8% and France with 1.7%.

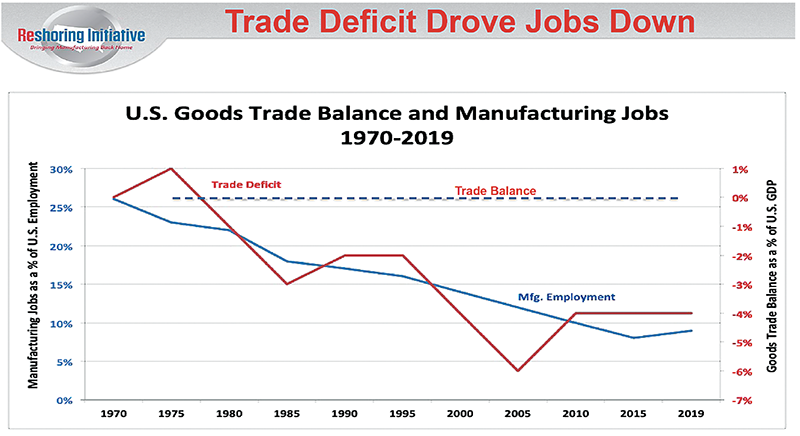

The accompanying chart, “Trade Deficit Drove Jobs Down,” shows China experiencing much of its growth over U.S. manufacturing between the years 2000 and 2010. Following the aught years, Moser said, there’s some gradual improvement for U.S. manufacturing, “albeit we’re losing jobs less rapidly.”

Moser added, however, that U.S. manufacturing managed to stanch the flow of jobs to China during the aught years. Since 2010, Moser has tracked all job announcements tied to reshoring and foreign companies investing in some way in manufacturing jobs on U.S. soil, otherwise known as foreign direct investment (FDI).

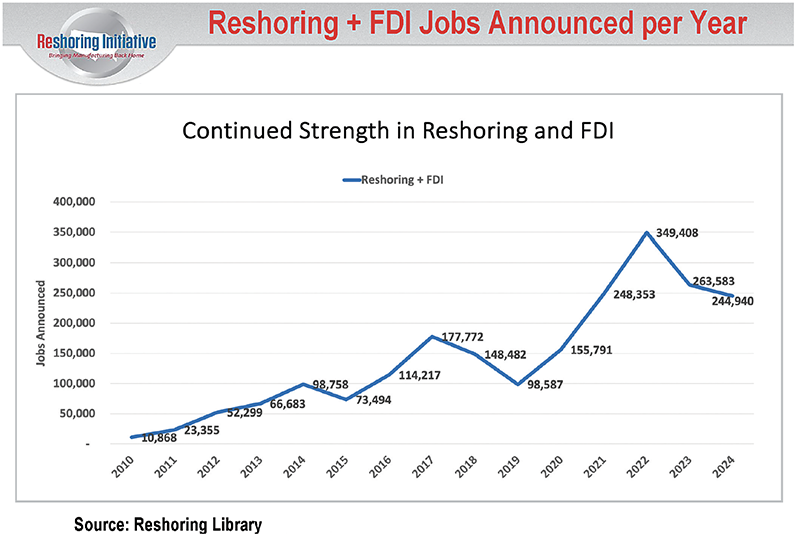

In fact, U.S. manufacturing jobs from reshoring and FDI reveals overall consistent growth since 2010. (See chart, “Reshoring + FDI Jobs Announced per Year” below.)

“The rate of job announcements has risen from 11,000 in 2010 to 240,000 in 2024, much better than anyone anticipated in 2010 when we were founded,” Moser observed.

Though the companies that have reshored or gone the FDI route have been able to find the workforce they need, he continued, other companies choose not to reshore directly because of the skilled labor shortage, further emphasizing the importance of workforce development efforts to alleviate the problem.

What’s more, a recent Reshoring Initiative survey of about 500 U.S. manufacturers found that “a sufficient quantity and quality of workforce” within the U.S. would bring back more manufacturing than any of the other surveyed options, Moser reported. A sufficient workforce was the clear favorite among the other options presented in the survey, which included tariffs, a lower value for the U.S. dollar, lower tax rates and fewer regulations.

The group as a whole said that a 15% additional tariff applied to everything from everywhere would help increase their output by 24%, Moser continued. By contrast, the same group said an abundant U.S. workforce with higher skills would on average increase their output by 30%.

“Having the right workforce,” Moser concluded, “would create about 2 million manufacturing jobs.”

The relationship between reshoring and workforce development is symbiotic, Moser stressed. “Reshoring needs a skilled workforce. A skilled workforce needs reshoring to succeed and prove the value of manufacturing careers.”

The skilled labor shortage not only hampers reshoring but could have long-term consequences for the U.S. economy. The Manufacturing Institute forecasts a workforce shortage of 1.9 million people by 2033.

“At such a level,” Moser said, “manufacturing will shrink by 10% and push automation much harder.” Still, Moser is quick to point out that technology alone cannot solve the workforce shortage. “We see automation as a necessary but not sufficient condition to enable reshoring,” he said. “Like in Alice and Wonderland, we need to run as fast as we can to stay even. So, automation and AI are not enough to enable reshoring but they are necessary.”

Battling an outdated perception

Changing the perception of manufacturing in this country usually is a reference to the public’s notion that manufacturing jobs are still dark, dirty and fraught with safety risks. But there’s also the idea that the industry is dying and, therefore, not worth mentioning as a career option to high school or college students. In fact, the pervasive view of manufacturing is so outdated, it’s jarring.

Comedian and talk show host Bill Maher questioned the desire to revive manufacturing in the U.S. during a March 2025 episode of his HBO series, Real Time with Bill Maher.

“Why do we want to bring back manufacturing? It’s so ’70s, I mean, that ship has sailed,” Maher said to his guests before noting the folly of trying to compete with clothing makers in other countries.

This perception, in a nutshell, is what the manufacturing industry must combat in order to chip away at the public’s resistance to manufacturing careers.

Facts about manufacturingAs of February 2025, the average hourly earnings among U.S. manufacturing production and nonsupervisory workers was $28.68, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For all manufacturing employees, average hourly earnings were $34.92. Foreign direct investment jumped from $757 billion in 2010 to $2.22 trillion in 2023, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In 2022, the manufacturing sector accounted for 42.4% of the total FDI position in the U.S. As of March 2025, U.S. manufacturing employment remained above pre-pandemic levels at 12.764 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s about 12,000 more jobs than in February 2020. |

At the heart of efforts to build a future U.S. manufacturing workforce are people like Iverson, whose mission is to change the public’s perception of manufacturing careers. “We need to reach not only the students, who simply don’t know that manufacturing careers are a viable option,” Iverson said, “but also parents who think that manufacturing is stuck back in the pre-computerization age.”

Unfortunately, noted Iverson, parents still clinging to the promise of college don’t bother to weigh the extreme cost of a four-year degree against the earning potential of the jobs for which their children are being trained. Manufacturing careers, he added, not only offer a well-paying alternative straight out of high school, they provide benefits such as paying for higher education.

“Today’s manufacturers,” he explained, “are more than willing to help pay to educate or upskill their future employees and leaders.”

Iverson has employed a variety of strategies to reshape the narrative around manufacturing, including publishing two books, creating a series of educational videos, awarding scholarships, and launching a podcast. Most recently, CHAMPION Now! introduced Camp CHAMP, a hands-on workshop designed to introduce middle school students to modern manufacturing environments. “The program is very much in its infancy with only 12 camps held,” Iverson noted, but added, “we have received great initial feedback from the high school mentors as well as career and technical education instructors who help run the workshops.”

Studies support the value of early exposure to manufacturing careers. One study conducted by the Student Research Foundation, in collaboration with The Manufacturing Institute, found that 63% of students who had enrolled in career and technical education courses credited their own interests and prior exposure to the industry as major influences on their career decisions.

Sweatman echoed the importance of early engagement for the next generation of skilled labor. “We typically will have about a dozen middle and high school tours each year (at SMT),” Sweatman said.

“We have had some success in getting some good hires from those,” Sweatman said. The hardest part of the school tours, he added, occurs when he learns about students who were excited about manufacturing during the tour only to get a negative reaction from their parents afterward. “I haven’t been able to figure out how to get to most parents.”

Iverson wrote his second book specifically to engage students and their parents at the same time. Beginning with its subtitle, “Discover The Path to a Debt-free Career,” the book lays out the case for putting manufacturing careers back on the radar in this country.

One book, or one voice, however, cannot by itself erase the emphasis this country has placed on higher education. That focus has clearly come at the expense of manufacturing careers, which are still not widely mentioned as an option for high school students to consider. For that matter, several generations of youth in this country have had little exposure to the manufacturing industry, let alone the careers it offers.

Why is that important?

A Kronos 2018 Manufacturing Day survey found that only 49% of parents were likely to encourage their child to consider a career in manufacturing, compared to 88% for technology and 82% for engineering. Other surveys have shown more than a fifth of parents still associate manufacturing jobs as outdated and dirty work environments, while a quarter of parents don’t think manufacturing pays well.

Another survey collaboration between Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute in 2022 suggested some improvement in the perception of manufacturing careers held by parents. Of the parents surveyed, 64% agreed that U.S. manufacturing jobs are creative, innovative and employ problem-solving skills, which was up from 39% in 2017. Plus, 40% of parents said they are likely to encourage their child to pursue a career in manufacturing, which was up from just 27% in 2017.

Whether the needle has moved on the perception of manufacturing careers among parents, reaching parents to update their perceptions about manufacturing careers remains a significant challenge, Iverson said, noting that more industry involvement will be needed to reach parents.

“Industry leaders need to get engaged,” Iverson said. “They need to become active participants with their high schools and promote internships at their companies.”

Sweatman emphasized the need for industry collaboration to overcome the labor shortage. “Industry collaboration is very important,” he said. “Unfortunately, it is a struggle to get manufacturers to take time away from their businesses to do so. If all machine shops had apprenticeship programs, the skilled labor shortage would go away.”

SMT works closely with local technical colleges and school systems to develop apprenticeship programs and training curricula. “We worked with [Pinellas Technical College] to convert the CNC apprenticeship from time-based to a hybrid with reduced hours and a certain number of NIMS credentials,” Sweatman said.

Funding obstacles

Funding remains a persistent challenge for workforce development initiatives like CHAMPION Now! “Most of it for the last 12 years has come from both myself and board members,” Iverson said. “During IMTS 2024, we received a five-figure donation from a very large machine tool distributor. The only way we can make an impact is to print and distribute books, produce podcast interviews, and conduct camps.”

The Illinois Manufacturing Excellence Center (IMEC) has funded Camp CHAMP for two years, but is potentially slated to be eliminated by recent cuts.

“Camp CHAMP is a great initiative,” said Sweatman, “but it is costly to ship the machines around the country. What would work better — if enough people got involved and supported it — would be to have regional locations with a set of machines that could more easily be transported to various locations to hold the camps.”

CHAMPION Now! calls this manufacturing localism.

“The skilled labor shortage will not go away unless everyone gets involved,” Sweatman continued. “One small initiative like CHAMPION Now! cannot do it by itself unless it gets enough support from industry.”

Informing and engaging younger generations about manufacturing careers through early exposure, modernized vocational education, and collaborative community efforts can positively influence their career choices. These strategies not only address the skilled labor shortage but also ensure a robust future workforce for the U.S. manufacturing industry. But as all three leaders make clear, the manufacturing industry itself must step up, collaborate, and invest in the next generation of skilled workers — before the opportunity to bring jobs back home slips away. CTE

Related Glossary Terms

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

electrical-discharge machining ( EDM)

Process that vaporizes conductive materials by controlled application of pulsed electrical current that flows between a workpiece and electrode (tool) in a dielectric fluid. Permits machining shapes to tight accuracies without the internal stresses conventional machining often generates. Useful in diemaking.

- lathe

lathe

Turning machine capable of sawing, milling, grinding, gear-cutting, drilling, reaming, boring, threading, facing, chamfering, grooving, knurling, spinning, parting, necking, taper-cutting, and cam- and eccentric-cutting, as well as step- and straight-turning. Comes in a variety of forms, ranging from manual to semiautomatic to fully automatic, with major types being engine lathes, turning and contouring lathes, turret lathes and numerical-control lathes. The engine lathe consists of a headstock and spindle, tailstock, bed, carriage (complete with apron) and cross slides. Features include gear- (speed) and feed-selector levers, toolpost, compound rest, lead screw and reversing lead screw, threading dial and rapid-traverse lever. Special lathe types include through-the-spindle, camshaft and crankshaft, brake drum and rotor, spinning and gun-barrel machines. Toolroom and bench lathes are used for precision work; the former for tool-and-die work and similar tasks, the latter for small workpieces (instruments, watches), normally without a power feed. Models are typically designated according to their “swing,” or the largest-diameter workpiece that can be rotated; bed length, or the distance between centers; and horsepower generated. See turning machine.

- metalcutting ( material cutting)

metalcutting ( material cutting)

Any machining process used to part metal or other material or give a workpiece a new configuration. Conventionally applies to machining operations in which a cutting tool mechanically removes material in the form of chips; applies to any process in which metal or material is removed to create new shapes. See metalforming.

- milling machine ( mill)

milling machine ( mill)

Runs endmills and arbor-mounted milling cutters. Features include a head with a spindle that drives the cutters; a column, knee and table that provide motion in the three Cartesian axes; and a base that supports the components and houses the cutting-fluid pump and reservoir. The work is mounted on the table and fed into the rotating cutter or endmill to accomplish the milling steps; vertical milling machines also feed endmills into the work by means of a spindle-mounted quill. Models range from small manual machines to big bed-type and duplex mills. All take one of three basic forms: vertical, horizontal or convertible horizontal/vertical. Vertical machines may be knee-type (the table is mounted on a knee that can be elevated) or bed-type (the table is securely supported and only moves horizontally). In general, horizontal machines are bigger and more powerful, while vertical machines are lighter but more versatile and easier to set up and operate.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

The Industry Needs You

|