For people prone to worry about the state of the economy going into 2020, there has been news that could exacerbate concerns. For example, in September the closely watched Purchasing Managers’ Index hit its lowest point since the Great Recession. The index, calculated by the Institute for Supply Management, Tempe, Arizona, declined to 47.8% that month. October’s figure — the last available before this article went to press — saw a 0.5 percentage point increase but remained under 50%, which is the demarcation line between economic contraction and expansion. Timothy Fiore, chair of ISM’s Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, said October marked seven straight months of contraction in manufacturing. In a news release, he stated that in that month all but one of PMI’s subindexes registered at levels associated with contraction.

Along with these developments have been scores of headlines about the slowing global economy and worries regarding the effects of tariffs and the ongoing trade war with China. Also, after a record economic expansion of 124 months — over twice as long as the average length of 60 months — isn’t the economy overdue for a recession anyway?

Come in from the ledge. The good news is that, while acknowledging definite headwinds, industry prognosticators nonetheless see a solid if not stellar year ahead for manufacturing.

“The Fed is anticipating that 2020 is going to be similar to what we’re experiencing right now — about a 2% growing economy,” said William Strauss, senior economist and economic adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. “Which will be decent but not impressive, kind of trendlike. It’s like getting a B on your report card.”

He said the contraction needs to be viewed in context of what’s come before, namely huge growth. The 2% growth rate in 2019 is quite a step down from 2.9% in 2018, he said. However, 2018 benefited from the tax reform stimulus passed at the end of 2017.

The stimulus “kind of gave a sugar high hit to the economy that got us growing a bit more rapidly,” Strauss said. “But like all sugar highs, we came off of it. And we’re heading back down to the more trendlike rate of growth.”

Eli S. Lustgarten, president of ESL Consultants Inc., St. Louis, said the impact of the 2018 boom was so strong that almost every industrial sector built up a backlog of orders.

“They couldn’t ramp up production fast enough” to meet the jump in demand, he said, meaning that orders will trail shipments in most markets heading into 2020. “They’re shipping to fulfill backlogged orders, but new orders have softened. Therefore, we’re looking at a peak of production. Production cuts are coming, and (production) will continue to decline into 2020. Next year will be a softer year in manufacturing. There’s little debate about that. But not terrible.”

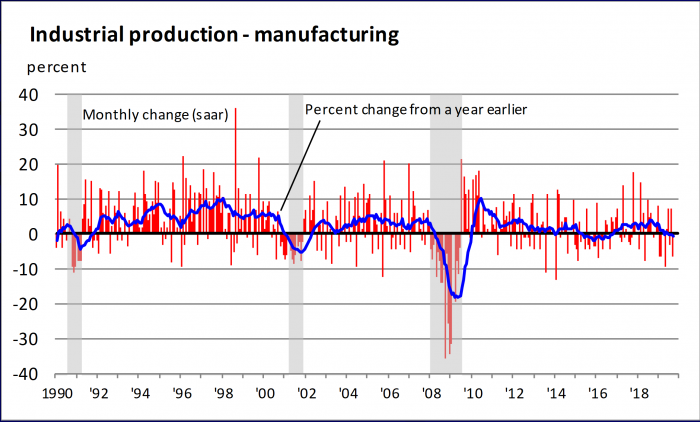

Current data puts manufacturing output growth at slightly below zero. Image courtesy of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

With industrial production probably continuing to be sluggish for the foreseeable future, cutting tool demand will weaken in response, Lustgarten said.

“Month-over-month demand has been volatile through most of 2019 but has trended downward since January,” he said. “We can expect cutting tool activity to continue to decelerate if not actually contract for the remainder of 2019 and likely into next year.”

Automotive and Aerospace

“Not terrible” isn’t exactly high praise, Lustgarten acknowledged, so he elaborated using the automotive sector as an example. Year-to-date sales of light vehicles in the U.S. have been 17 million.

“It’s been running at very high levels for the last couple of years,” he said. “The industry expectation is that over 17 million is above normal. So now it will trend downward to a more normal rate. The forecast for 2020 is in the 16.5 million range for sales and production, which is down but still mighty good.”

The aerospace market, despite distressing headlines about Chicago-based Boeing Co.’s 737 Max airplane, is also solid, said Richard Aboulafia, vice president of Teal Group Corp., Fairfax, Virginia. As of mid-2019, both Boeing and Airbus Group, Leiden, Netherlands, had backlogs of firm orders: $444 billion for Airbus and $393.6 billion for Boeing. The industry is enjoying low interest rates, as well as a sweet spot for fuel prices.

“When fuel prices are high, ticket prices go up and/or airlines lose money,” he said. “On the other hand, when fuel is cheap, airlines will tend to hang on to older planes. They don’t have as much incentive to invest in lighter, more fuel-efficient models.”

Besides the industry being in a Goldilocks zone of “just right” for interest rates and fuel prices, Aboulafia said strong defense spending is helping.

Regarding the 737 Max, he pointed out that although deliveries are stalled while a safety investigation plays out, production of the plane has slowed but not stopped. He expects any technical issues to be resolved within about a year, though political complications may linger longer. More importantly, he doesn’t anticipate the issue to result in further major cancellations or deferrals.

“The Max is still a 12- to 14-year program,” Aboulafia said.

Global Headwinds

In addition to the tax stimulus wearing off, Strauss said the big change to the economy has been “a ramped-up headwind coming from the trade story. We began seeing tariffs put on the economy in early 2018 — steel, aluminum and appliances — but the economy largely seemed to absorb the initial jolt. But as we moved into 2019, there was a lot of stepped-up rhetoric of additional tariffs coming.”

That rhetoric has caused uncertainty for manufacturers as they’ve tried to figure out their global supply chain logistics.

“They had to wonder how long would these tariffs persist?” Strauss said. “Would they change further? Would another country be added in? Questions that made planning extremely difficult.”

He said manufacturers have responded the way businesses typically do when faced with uncertainty: by delaying every decision they can delay. The result has been a drop-off in capital spending.

Along with the tariff issue are concerns about the ailing global economy.

“It’s not that the weakness that we’re seeing in our manufacturing sector is because some other part of the world is eating our manufacturers’ lunch,” Strauss said. “In fact, most manufacturers around the world are really struggling.”

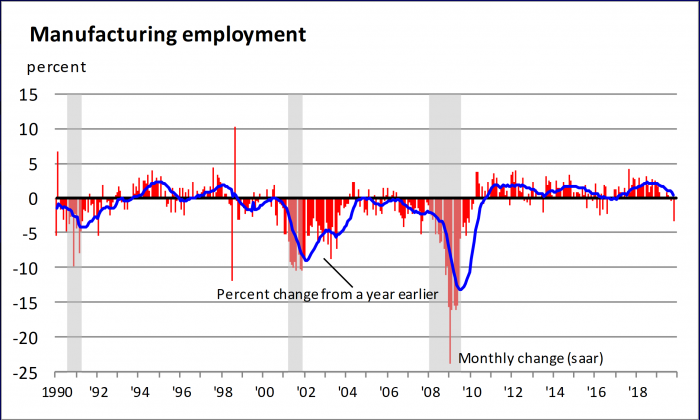

Manufacturing employment increased by 49,000 workers in the 12 months after September 2018. Image courtesy of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

He said Germany is probably in the worst position, with PMI figures showing that manufacturing in that country has been in the recessionary range for about seven months. And because Germany’s economy is a big engine for Europe’s economy, there are worries about potentially weak European performance affecting U.S. exports going into 2020.

Given how challenging global growth is now, “we might not be happy with trend growth here, but we’re still, all in all, the envy of the rest of the world,” Strauss said.

Domestic Tail Winds

There are positive influences on the economy too. These include still solid consumer spending and job growth, a pickup in residential investment and continued monetary easing, said Erik Lundh, senior economist at The Conference Board Inc., New York City. He expects consumer spending to soften slightly in the coming quarters but to keep propping up economic growth.

“Job growth remains on a slowing trend but is still growing fast enough to further tighten the labor market,” he said. “The unemployment rate now stands at a 50-year low.”

Gad Levanon, head of The Conference Board’s Labor Markets Institute, sees good news in the most recent employment numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, pointing out that total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 128,000 in October.

“This is a stronger than expected gain given the negative impact from the GM strike,” he said, “which probably lowered overall employment by more than 50,000.”

The numbers for August and September were revised up significantly as well, Levanon said, showing that the trend in employment growth is higher than expected, probably in the range of 150,000 to 200,000. Such statistics portend a labor market that continues to tighten, which has the effect of pulling more people into the workforce, including those from underrepresented demographic groups.

“With such solid employment growth,” he said, “consumer spending is likely to remain strong into the holiday season and keep the U.S. economy growing despite cautious spending by businesses.”

Also helping the economy are low interest rates. Strauss cited the Fed’s three interest rate cuts in the latter half of the year.

“That should probably add a little bit of wind to the sails of the economy and hopefully bring our inflation rate, which has been below the target of 2%, up closer to that target as we go into next year,” he said.

The interest rate situation should make consumers less wary when buying big-ticket items and let manufacturers invest more easily in capital equipment. And as for the longest economic expansion in U.S. history, there is no inevitable end.

“A lot of people note that the average expansion is about five years, or 60 months, and as we’ve gone twice that long now, we’re due for a recession,” Strauss said. “But that’s not how recessions happen. Nobody gets tired of making money. Nobody gets tired of growing. What actually happens is that the economy gets some kind of negative economic shock, and if it is bad enough, recession follows. But when it isn’t that bad, the economy recovers and keeps growing.”

He mentioned the equity market crash in fall 2018 as an example.

“The collapse led to a 20% drop in the stock market (in) the fourth quarter last year,” Strauss said, “and there were people out there saying, ‘Ah, here comes a recession. The time has come.’ And of course it just didn’t turn out to be that way.”

Recessions occur because of drastic events, not the flipping of a certain number of calendar pages. He said the Fed expects growth to continue at about a 2% rate through 2022.

Related Glossary Terms

- sawing machine ( saw)

sawing machine ( saw)

Machine designed to use a serrated-tooth blade to cut metal or other material. Comes in a wide variety of styles but takes one of four basic forms: hacksaw (a simple, rugged machine that uses a reciprocating motion to part metal or other material); cold or circular saw (powers a circular blade that cuts structural materials); bandsaw (runs an endless band; the two basic types are cutoff and contour band machines, which cut intricate contours and shapes); and abrasive cutoff saw (similar in appearance to the cold saw, but uses an abrasive disc that rotates at high speeds rather than a blade with serrated teeth).

Contributors

The Conference Board Inc.

212-759-0900

www.conference-board.org

ESL Consultants Inc.

201-926-9099

www.eslconsultants.net

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

312-322-5322

www.chicagofed.org

Teal Group Corp.

888-994-8325

www.tealgroup.com