Deshazo Crane Co. is a manufacturer of overhead cranes and custom automation equipment. Last summer, after receiving a number of large orders for automated equipment, the company’s machine shop found itself overwhelmed with the amount of parts it needed to make. A sales rep remembered hearing about a website that helped connect customers and suppliers of machining services—MFG.com. He casually suggested it as a possible solution. That water-cooler conversation wound up changing the way the company did business.

“We registered for an account and almost immediately got a phone call from MFG.com’s customer support team,” said Daniel Drennen, project manager at Deshazo, Alabaster, Ala. “I was surprised by their responsiveness and struck up a conversation with their representative.”

While Deshazo had some initial concerns regarding quality and affordability, the first delivery of parts quickly put those to rest. From that point forward, the company’s president of automation decreed all future subcontracting would go through that website.

That’s a great story—but what exactly makes this type of website worthwhile?

New Kind of Marketplace

“The fundamental thing is that it’s a marketplace,” said Chris Mitchell, chief marketing officer for Marietta, Ga.-based MFG.com. Bringing buyers and suppliers together may not be unique in and of itself, but Mitchell believes his company has a distinct edge in terms of scale.

“I’m not aware of too many other contract manufacturing marketplaces with global reach,” he said. “We not only bring OEMs and suppliers together from all over the world, we provide the tools to enable the interaction. It’s almost a matchmaking service for manufacturing companies.”

For a fee—typically $300 to $600 per month—suppliers can bid on request for quotes for virtually anything, from simple components to complex, tight-tolerance specialty parts to full assemblies. Buyers can create and post RFQs free of charge.

“I have not been able to convince our shop to place an entire control panel on the marketplace for bid,” said Deshazo’s Drennen, “but based on our experience so far, I’m confident we would find qualified, competent vendors who would be able to complete the work.”

Pobody’s Nerfect

No system is without its shortcomings, and there are inherent risks, disadvantages and pitfalls to virtually everything. Online, direct-procurement marketplaces are no exception. And while Deshazo is a success story, a shop’s experience may vary considerably, depending on the desired results and the work it’s willing to put in.

For example, Tomball, Texas, contract manufacturer Crow Corp. has been using the internet to grow its business since the late 1990s. The company started with an online advertising package from Yahoo, at a time when that was the dominant search engine. Around 2001, the company became aware of more-specialized services and decided to take a chance.

“The internet was really catching on in a huge way around then, so lots of companies were selling services with the anticipation of the big boom,” said Keith Jennings, Crow president. “The prevailing notion was that there was lots of money and business to be made, which sounded good to us too.” [Editor’s note: Jennings is the author of CTE’s Manager’s Desk column.]

The site Crow selected was GlobalSpec.com. At the time, it was based on an early version of the concept refined by sites like MFG.com—a community of buyers and sellers where jobs could be listed and bid on.

“We tried it, but we found that we were paying less and getting more inquiries from our regular online listings, which also gave us more direct contact with our customers,” Jennings said. “The problem we found was that a lot of the buyers would put together an RFQ and send it out to numerous potential suppliers. That’s great for the buyer, because you only do the work once, but, as a supplier, we were always competing against a lot of other manufacturers, and it usually came down to nothing more than the lowest price.”

Crow’s pricing typically fell in the middle of the pack, he continued, and the shop wasn’t comfortable making significant sacrifices to either quality or profits to compete in that sort of marketplace.

“Our work is good, and our reputation will speak to that, but the way those systems were set up at the time, you didn’t really get to speak with the customer directly,” he said. “There was no way to negotiate or follow up or get another shot at the job. We just did not find a lot of value in that particular system.”

Crow eventually moved all of its online business to Google advertising, which still generates new business.

Manufacturing Tools

While Mitchell acknowledged Jennings’ concerns, he believes MFG.com has a system in place to help shops overcome those potential obstacles.

“Because it’s the internet, you can find yourself competing with shops all over the world, some of which are in countries where labor is incredibly cheap,” he said. “What we’ve seen from time to time is suppliers who think that when they join, it’s like turning on a spigot and new jobs will come falling into their laps; but it’s a competitive place and it’s a different way of pursuing business. You need to learn how it works in order to be successful.”

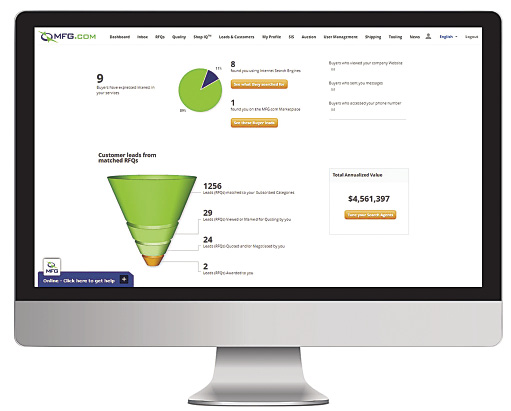

MFG.com provides free training to members to help them succeed in the environment. Mitchell said when companies don’t take advantage of that training, they tend not to be satisfied with the results. Suppliers can subscribe to the processes and geographic regions they’re interested in and filter the resulting RFQs so they only see jobs they might be interested in bidding on—based on factors such as workpiece materials, part sizes and run sizes.

However, setting those filters properly is complicated, and MFG.com’s training helps eliminate the trial and error that might cost parts manufacturers valuable business opportunities. The training also covers basic processes, such as submitting an RFQ, and best practices based on internal metrics, such as how often to log on to check for new job postings and how to best respond to messages.

“We have participated on the buyer side and the sales side [of MFG.com], and being on the sales side really makes you aware of your company’s strengths and weaknesses,” Deshazo’s Drennen said. “If you approach it with a positive attitude and a competitive spirit, you can stand to not just benefit financially, but actually improve your company.”

In addition to the marketplace and the training, MFG.com (like some of its competitors) provides a number of tools and feedback. One program, ShopIQ, measures a shop’s performance over time. After enough jobs have been quoted and completed for the data to be meaningful, shops can see what types of jobs they’re most successful performing. Deshazo, for example, excels at milling work and has found the most success bidding on jobs in the Midwest.

“What we do is go to buyers (potential users of contract machine services) and encourage them to bring these opportunities into the marketplace,” Mitchell said. “Because we put a lot of effort into developing good relationships with our buyers, we’re able to give our suppliers access to jobs that they might never be able to get on their own.”

While MFG.com sees its share of RFQs from inventors and engineering students looking for interesting, unusual parts, the site is also able to attract major corporate and government contracts that might be out of reach for many shops. “NASA just posted a number of parts,” Mitchell said, “and every single supplier on our site now has the opportunity to bid on a job for NASA. What we’re doing for shops, in return for their subscription fee, is using the connections we’ve built over the years and finding new business to bring directly to them.”

While not all shops will see a value in this type of service, those that do tend to view their membership as a fundamental aspect of their business.

“I’m speaking on the record with mixed emotions, because I really do believe that MFG.com brings a tremendous value to our shop,” Drennen said. “But as much as I want to spread the word and try to help them as much as they’ve helped us, the businessman in me doesn’t want any of our competition to find out what an advantage this can give.”

Relationships—More Than Matchmaking

“Some may see our service as a replacement for a sales rep, but I don’t think that’s a good way to look at it,” said MFG.com’s Chris Mitchell. “Getting this tool to a qualified salesperson is a very powerful combination, because it connects you directly with people in need of the specific services you can offer, which means you can skip almost directly to the point where you can start communicating and quoting.”

Sales reps can display their MANA credentials (above) on their office wall or in their email signature (below).

But not all sales forces are created equal. That’s where MANAonline.org, the official website for the Manufacturers’ Agents National Association comes in.

“Our mission is to provide manufacturers and reps the educational materials they need before they start the process of finding and interviewing each other, and to help make their relationships thrive over long periods of time,” said MANA President and CEO Charles Cohon.

The trade association’s most popular tool is RepFinder, a searchable database of MANA’s members who offer repping services. Print and online classifieds are also available in Agency Sales, the association’s monthly magazine.

However, identifying great candidates to represent manufacturers’ lines is only the first step. MANA manufacturers, Cohon explained, have access to tools and publications to help find and choose the right representative and craft a fair agreement.

“Without the educational component, the chances of success with reps are lower,” Cohen said. “While we can’t enforce manufacturers’ use of that component, we strongly encourage them to use it, and do not offer our rep-members’ names to manufacturers except through membership.”

Representatives tend to have intimate knowledge of their territories as a result of years, or decades, of experience, providing a distinct advantage over a short-time direct salesperson, who makes a 1- to 2-year stop in a territory before moving to a greener pasture, he noted. In addition, because reps are independent contractors, they allow manufacturers to avoid all the fixed costs of direct-sales employees, such as health insurance.

However, that’s also what makes the relationship between company and rep so important from the company’s perspective.

“Reps bring their customers’ relationships to their relationship with you, but you will find that those relationships stay with the rep and are not transferrable to you,” Cohon said.

—E. Jones Thorne

Contributors

Crow Corp.

(800) 642-2769

www.crowcorp.com

Deshazo Crane Corp.

(800) 926-2006

www.deshazo.com

Manufacturers’ Agents National Association

(877) 626-2776

www.manaonline.org

MFG.com

(888) 404-9686

www.mfg.com

Contact Details

Related Glossary Terms

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.