Ask any machine shop owner, production supervisor or human resources manager to name his or her biggest challenge, and you’re likely to hear the same answer: “We can’t find qualified people to set up and program our CNC equipment.” Isn’t it ironic then that so many manufacturing companies are turning to machine tools that are more complex rather than less—equipment that requires greater skills to operate and makes finding a machinist able to handle it even more difficult?

Help Wanted

“The elephant on every shop floor is the fact that the baby boomers are getting older and there aren’t enough people entering the trades to replace them,” said Carl Barthelson, regional sales manager at Doosan Machine Tools America, Pine Brook, New Jersey. “A case in point is the largest jet engine manufacturer in North America. The company is experiencing its largest jet engine backlog ever, but 30 percent of its workers will reach retirement age within 5 years. Now what?”

Image courtesy of Doosan Machine Tools America

Companies have two ways to combat this problem, he said. Businesses can attempt to poach employees from competitors, a move that might be good for machinists’ wages but bad for company profits. Or organizations can automate their processes. He said the best way to automate is with a multitask machine tool. Because multitaskers reduce the number of machining steps—often completing workpieces in a single setup—shops have less need for fixturing, decreased work in process and improved part quality.

In that regard, it appears that the most complex machine tools found on any shop floor make everything about manufacturing life simpler.

These expensive machine tools aren’t for only large manufacturers. Barthelson cited a five-person machine shop in western Pennsylvania whose owners went out on a financial limb several years ago by investing in a $400,000 mill/turn center. Today, the machine is at full capacity and the shop is considering a second such multitasker.

“When they were just a typical job shop filled with 2-axis lathes and 3-axis machining centers, they had to bid everything at $50 an hour,” he said. “Because they’re able to solicit more difficult work and parts with tighter tolerances and machine those parts in less time, they’re now quoting at three times that rate.”

Revisiting IMTS

Success in the machining world is no longer about keeping up with the Joneses—it’s about blowing their doors off. Perhaps one way to do this is to adopt and invest in the most advanced manufacturing technologies available, multitaskers among them.

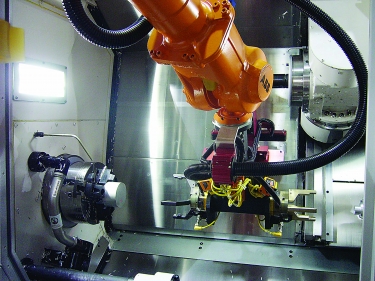

As qualified machine tool operators become increasingly difficult to find, automation takes a commensurately larger role. Image courtesy of Okuma America

The industry is listening. Anyone who attended the International Manufacturing Technology Show in September can attest that the number and variety of multitask machine tools is staggering:

- Doosan introduced a number of models, including a “super” series of multitask machines that come with a lower turret for additional flexibility and increased throughput.

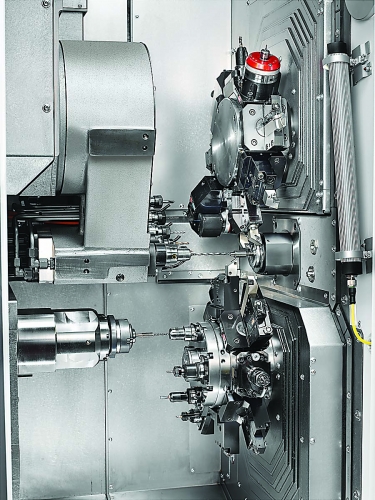

- INDEX Corp., Noblesville, Indiana, demonstrated a Traub 11-axis TNL20 lathe equipped with automated part handling and an INDEX MS40C-8 8-spindle automatic, which was able to complete two complex parts per cycle.

- Ganesh Machinery, Chatsworth, California, showed its flagship 32-CS 7-axis Swiss-style lathe and the Genturn SL42Y2 42mm, dual Y-axis multitasker.

- Charlotte, North Carolina-based Okuma America Corp. demonstrated everything from laser-equipped hybrid multitaskers to machines capable of gear cutting and skiving.

Then there was the automation. Tim Thiessen, vice president of sales and marketing at Okuma, said robots are reaching far beyond their familiar role of part loading and unloading. They can handle part inspection, deburring and changing tools, greatly expanding the capabilities of machines that were already quite capable.

“There’s definitely a strong push toward all forms of automation,” he said. “Much of that is driven by a surge of reshoring to the United States, coupled with the fact that it’s very difficult to find machinists. This means you need robots able to perform tasks once reserved for humans, as well as machines that can do more with less operator intervention.”

Making Robots Do More

One example of this shift is a robot able to change Capto-style turret tooling or load and unload toolholders that are too long or heavy for a multitasker’s automatic toolchanger, expanding the machine’s lights-out capabilities. The same robot might be called upon to place finished workpieces on a nearby coordinate measuring machine, after which the machine control can decide whether to perform a tool offset or call up a replacement one.

This twin-spindle, twin-turret machine from INDEX is just one of the dozens of available multitask configurations. Image courtesy of INDEX

Asking robots to go above and beyond parts loading can present challenges. Handling complex, oftentimes very expensive finished workpieces requires a careful, accurate grip, far more so than when sticking a raw material blank into an 8" chuck. Because a robot is now being asked to manipulate toolholders, as well as workpieces, it needs an automated way to change grippers. And because multitaskers often contain multiple turrets and spindles—never mind a bigger footprint—a robot must have the reach and flexibility to address larger work areas than in the past.

Thiessen recommended that shops think carefully about their future needs before investing in any machine tool technology. “There are way too many people who take their first step into multitasking with a machine that has a small tool capacity or a limited set of options,” he said. “They quickly discover the many benefits of multitasking and then kick themselves for not buying a more capable machine.”

Industry 4.0 Included

Tyler Economan, customer support and operations manager at INDEX, agreed that robots are a great addition to any multitask machine. “Everyone knows that there’s a skilled labor shortage, one that most predict we’ll be dealing with for the foreseeable future,” he said. “This makes it especially important to have machines that can do more with less—less space, less people, less overhead. Multitaskers and multispindle machines accomplish this. By adding a robot to handle the menial tasks like cleaning parts or loading them into a measurement fixture, you’re increasing the efficiency and flexibility of what was already a very capable machine tool.”

The line between the first multitask machines—Swiss-style lathes—and newer mill/turn centers continues to blur as machine tool builders eliminate the need for guide bushings. Image courtesy of Ganesh Machinery

Increased capabilities aside, there’s more to successful multitasking than high-quality machine tools and robots. Shops must also become extremely organized if they’re to efficiently manage more jobs, more tools and lengthier and more complex CNC programs—all with fewer people.

INDEX hopes to make organizing a little easier with iXworld, a web-based portal to give customers easy access to everything they need to know about their machine tools. An extension of the company’s “i4.0 ready” iXpanel operating system, iXworld allows its customers to order parts, request service, observe statistics and provide online feedback about machine performance.

The online portal “gives customers the information they need to run their business in a better way,” Economan said. “It also provides a basic platform for potential future services. For instance, we’re doing more with smart glasses and augmented reality, a technology that will make it easier for us to support customers remotely with maintenance or setup tasks. We recognize that, as Industry 4.0 grows, there may be other applications we can capitalize on to provide better knowledge about our machine tools and new ways to make them even more profitable.”

Win-Win

Unfortunately, the more capable the machine, the higher the price tag. Ravjeet Singh, vice president of sales at Ganesh Machinery, and Marketing Manager Kamal Grewal hope to make multitasking a little more affordable by partnering with control builder Mitsubishi Electric Corp.

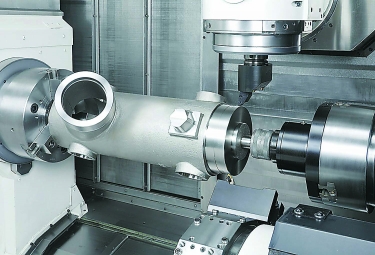

The lower turret is often used for simultaneous machining, as in this example, but can also be used as a steady rest to

support long workpieces. Image courtesy of Okuma America

“One of the challenges everyone faces is that, by the time you add all the different axes and features needed in a multitasking machine, the control costs can become quite high,” Singh said. “Mitsubishi has recognized this, which is why we’ve been able to bundle their most powerful control with a 3-year bumper-to-bumper warranty.”

Another obstacle is training. Singh said the initial response by many machine operators facing a machine tool with seven or more simultaneous axes is a sense of horror.

“They take one look and say, ‘You really expect me to run that thing?’” he said. “That’s why it’s very important for shops who are just starting out to find a machine tool supplier that can support them for the long haul and is willing to work with them until they’re 100 percent comfortable.”

Singh noted that if a customer needs additional training later, it’s free at Ganesh’s Chatsworth facility for the life of the machine.

Making customers as comfortable with multitaskers as they are with basic 2-axis lathes is not as difficult as it might seem, Singh explained. “It’s really not that different than what they’ve been doing. You set up the tools, you program the left side of the part, the right side of the part, and then sync the two together. Once one of our application engineers walks someone through it a couple times, they’re sold. They see how much the cost of production goes down with multitasking machines and how much more money there is in their pockets at the end of the day. It’s not long before they’re thinking about a second or third machine.”

Related Glossary Terms

- automatic toolchanger

automatic toolchanger

Mechanism typically included in a machining center that, on the appropriate command, removes one cutting tool from the spindle nose and replaces it with another. The changer restores the used tool to the magazine and selects and withdraws the next desired tool from the storage magazine. The changer is controlled by a set of prerecorded/predetermined instructions associated with the part(s) to be produced.

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- chuck

chuck

Workholding device that affixes to a mill, lathe or drill-press spindle. It holds a tool or workpiece by one end, allowing it to be rotated. May also be fitted to the machine table to hold a workpiece. Two or more adjustable jaws actually hold the tool or part. May be actuated manually, pneumatically, hydraulically or electrically. See collet.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- fixture

fixture

Device, often made in-house, that holds a specific workpiece. See jig; modular fixturing.

- lathe

lathe

Turning machine capable of sawing, milling, grinding, gear-cutting, drilling, reaming, boring, threading, facing, chamfering, grooving, knurling, spinning, parting, necking, taper-cutting, and cam- and eccentric-cutting, as well as step- and straight-turning. Comes in a variety of forms, ranging from manual to semiautomatic to fully automatic, with major types being engine lathes, turning and contouring lathes, turret lathes and numerical-control lathes. The engine lathe consists of a headstock and spindle, tailstock, bed, carriage (complete with apron) and cross slides. Features include gear- (speed) and feed-selector levers, toolpost, compound rest, lead screw and reversing lead screw, threading dial and rapid-traverse lever. Special lathe types include through-the-spindle, camshaft and crankshaft, brake drum and rotor, spinning and gun-barrel machines. Toolroom and bench lathes are used for precision work; the former for tool-and-die work and similar tasks, the latter for small workpieces (instruments, watches), normally without a power feed. Models are typically designated according to their “swing,” or the largest-diameter workpiece that can be rotated; bed length, or the distance between centers; and horsepower generated. See turning machine.

- multifunction machines ( multitasking machines)

multifunction machines ( multitasking machines)

Machines and machining/turning centers capable of performing a variety of tasks, including milling, drilling, grinding boring, turning and cutoff, usually in just one setup.

- steady rest

steady rest

Supports long, thin or flexible work being turned on a lathe. Mounts on the bed’s ways and, unlike a follower rest, remains at the point where mounted. See follower rest.

- toolchanger

toolchanger

Carriage or drum attached to a machining center that holds tools until needed; when a tool is needed, the toolchanger inserts the tool into the machine spindle. See automatic toolchanger.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

Contributors

Doosan Machine Tools America

973-618-2500

www.doosanmachinetools.com

Ganesh Machinery

818-349-9166

www.ganeshmachinery.com

INDEX Corp.

317-770-6300

www.indextraub.com

Okuma America Corp.

704-588-7000

www.okuma.com