High-performance cutting tools can provide increased efficiency and productivity, but they can also be a drain on tooling budgets. Cost-justifying these tools often requires regrinding and reconditioning them when they are worn or damaged. A successful reconditioning program reduces tooling costs by extending life as long as possible.

While costly, high-performance cutting tools and advanced machine tools are needed when performing high-speed machining, hard milling, thread milling and helical pocketing—operations that were uncommon in the not-too-distant past. These machining processes require cutting tools produced to exacting standards and close tolerances, which increases the complexity of the reconditioning process.

Reconditioning has grown so complex that is rare to find a shop that does not send its tools to a reconditioning shop. That’s because reconditioning high-performance cutting tools requires more than a conventional tool and cutter grinder and a pot of hot wax. Multiaxis CNC tool grinders and superabrasive wheels have replaced Monoset grinders and vitrified wheels.

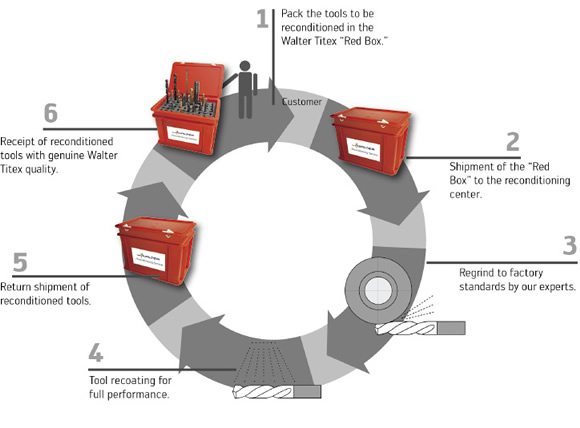

A description of the Walter Titex tool reconditioning program. Walter is one of the cutting tool suppliers at Savannah Machinery Works.

Therefore, successful reconditioning requires finding and partnering with the right reconditioning company, and it may require partnering with more than one. In most cases, a good cutting tool distributor can usually help you find one or more suppliers with good reputations.

Complex tool geometries, multilayer coatings and demanding tool manufacturing processes are often closely guarded secrets. In some cases, only the tool manufacturer can accurately recondition its tools, and most major toolmakers provide reconditioning services that return tools to OEM specifications and come with a performance guarantee. Take advantage of their expertise and willingness to absorb the risk of improper reconditioning.

A reconditioning program that maximizes cost benefits must be thoughtfully developed and actively managed. Correct tool application in the machining process is the first step toward developing a successful reconditioning program.

Major toolmakers provide engineering support and typically help develop efficient machining processes. Engaging toolmakers and learning to properly apply their tools helps prevent damage caused by misuse. Damaged flutes and chipped corners can quickly cause catastrophic tool failure and possibly scrap the part being machined. In addition, damaged tools cost more to recondition than worn tools since regrinding them is more complicated.

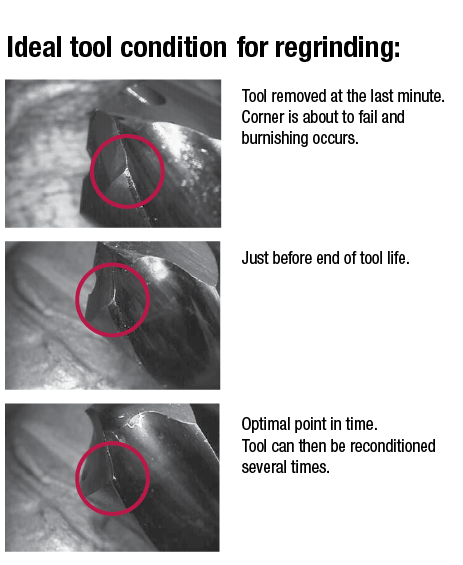

Shop personnel must also be trained to watch for increasing burr size, poor surface finish and dimensional changes, all signs of worn tools. Being able to identify cratering, plastic deformation, flank wear and other wear patterns enables the operator to intervene and make adjustments that prolong tool life.

Rely on guidance from the toolmaker to develop a training program—often free of charge—so shop personnel can learn to recognize the signs of worn tools and properly determine wear patterns. A robust training program allows personnel to correctly determine the proper time for removing a tool from service, which not only prevents costly tool and part damage but also premature tool removal (see graphic below).

Reconditioned tools should perform as well as new tools. If there is a performance drop after reconditioning, it may be time to look for a different vendor. Even a large savings in the reconditioning cost per tool can be eclipsed by the cost of lost productivity from an improperly reconditioned tool. Shop personnel often avoid using reconditioned tools that perform poorly, defeating the purpose of reconditioning.

Clear communication with the reconditioning company helps ensure tools are returned in the desired condition. Sending a box of worn, broken and jumbled tools to the reconditioner without instructions is a recipe for failure.

Clearly define the requirements for each tool and include instructions as part of the purchase order. Also, include contact information for the person at your shop who can answer technical questions. Package the tools properly to prevent damage during transport, ideally using the original container. The label on the original container identifies the original specifications, helping to eliminate errors. This is especially critical when the tool has features such as corner radii, steps or tapers.

Develop and distribute shop processes for tracking reconditioned tools. Shop personnel should be able to easily distinguish reconditioned tools from new ones. Putting a reconditioned tool into a machining operation and not accounting for differences in tool size can result in expensive rework, damage to other tools and possibly scrap.

Developing an effective reconditioning program will reduce costs and increase productivity, but it requires proper planning, comprehensive training and strong vendor support. Developing such a program takes time and requires input from multiple departments in the organization. Active management is needed to maintain success. Visit the shop floor to observe the handling of tools, track performance and analyze the costs to gauge program success. CTE

About the Author: Christopher Tate is manufacturing engineering lead for machining at Mitsubishi Power Systems, Savannah (Ga.) Machinery Works, a global builder of gas and steam turbines. He has 19 years of experience in the metalworking industry and holds a Master of Science and Bachelor of Science from Mississippi State University. E-mail: [email protected].Related Glossary Terms

- burr

burr

Stringy portions of material formed on workpiece edges during machining. Often sharp. Can be removed with hand files, abrasive wheels or belts, wire wheels, abrasive-fiber brushes, waterjet equipment or other methods.

- computer numerical control ( CNC)

computer numerical control ( CNC)

Microprocessor-based controller dedicated to a machine tool that permits the creation or modification of parts. Programmed numerical control activates the machine’s servos and spindle drives and controls the various machining operations. See DNC, direct numerical control; NC, numerical control.

- cratering

cratering

Depressions formed on the face of a cutting tool caused by heat, pressure and the motion of chips moving across the tool’s surface.

- flank wear

flank wear

Reduction in clearance on the tool’s flank caused by contact with the workpiece. Ultimately causes tool failure.

- flutes

flutes

Grooves and spaces in the body of a tool that permit chip removal from, and cutting-fluid application to, the point of cut.

- gang cutting ( milling)

gang cutting ( milling)

Machining with several cutters mounted on a single arbor, generally for simultaneous cutting.

- metalworking

metalworking

Any manufacturing process in which metal is processed or machined such that the workpiece is given a new shape. Broadly defined, the term includes processes such as design and layout, heat-treating, material handling and inspection.

- milling

milling

Machining operation in which metal or other material is removed by applying power to a rotating cutter. In vertical milling, the cutting tool is mounted vertically on the spindle. In horizontal milling, the cutting tool is mounted horizontally, either directly on the spindle or on an arbor. Horizontal milling is further broken down into conventional milling, where the cutter rotates opposite the direction of feed, or “up” into the workpiece; and climb milling, where the cutter rotates in the direction of feed, or “down” into the workpiece. Milling operations include plane or surface milling, endmilling, facemilling, angle milling, form milling and profiling.

- plastic deformation

plastic deformation

Permanent (inelastic) distortion of metals under applied stresses that strain the material beyond its elastic limit.