Many small manufacturing companies think of automation as being appropriate for low-mix, high-volume manufacturing and assembly. It’s fine for, say, Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Co. but not for what they themselves do. That mind-set, however, is increasingly out of date, according to automation developers and their customers. Automation is now being embraced by manufacturers that eschewed it in the past.

Beyond Automotive’s Top Tiers

“For decades, robots were synonymous with large-scale automation in automotive factories around the world,” said Per Vegard Nerseth, head of the robotics business unit at ABB Inc., Zurich. He noted, however, that, according to the International Federation of Robotics, the electronics industry accounted for almost as many shipments of robots as the automotive industry in 2016. “The electronics sector now accounts for as much as 90 percent of the sales of new, more precise robots that can assemble small parts. We expect this trend to continue, and even accelerate, in the future.”

Image courtesy FANUC America.

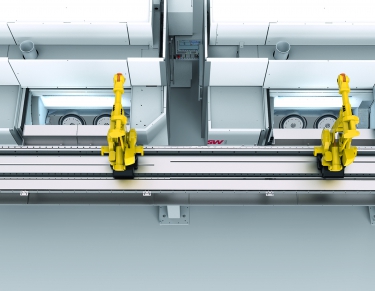

Concurrently, high-mix, low-volume job shops are finding that automation can add value after all. SW North America Inc., New Hudson, Mich., which builds multispindle machining centers, reports that more and more customers are interested in acquiring automation. In response, SW started offering automation just 2 years ago, according to Chief Sales Officer Jim Campbell.

“I would say that 80 percent of the inquiries we get are from companies that want automation of some sort,” he said. Most SW sales are still for high-volume systems, he explained, but that’s changing. “Customers are looking for turnkey systems. They’re looking for the machines, the automation, often the gaging and everything else, and they want it from a single, trusted source, because most of the smaller shops don’t have the resources to put all of those things together. It’s a new game for us.”

Kevin Ostby, vice president of FANUC America Corp., Rochester Hills, Mich., said automation use by smaller, high-mix, low-volume shops has been happening on a modest scale all along. “It’s happening at a greater scale now, but it’s incremental compared to the volume portion of the market. The growth is dramatic, but the scale is still relatively small. As smaller shops continue to adapt and to utilize and understand the technology and are no longer afraid of it, it’s going to multiply even more dramatically.”

The Waiting

There are good reasons why small and medium-size shops have passed on automation in past years—and good reasons why they are beginning to change their minds. A top reason for hesitating, according to Campbell, has been sticker shock.

Campbell explained that, in the past, shop owners would think that spending $200,000 on automation adds complexity and consumes floor space. They could hire a guy to load and unload the machine for $12 an hour, so why change? “Those days are gone,” Campbell added. “The business is more competitive, and you can’t find the $12 an hour guys.”

Another reason shops have been slow to automate is their lack of knowledge and comfort with what state-of-the-art automation can do for them. Ostby compared this challenge to the rollout of the personal computer. He said when the PC first came on the market, a lot of people were afraid of it because it seemed overwhelming. They were confronted with a monochrome screen displaying, for example, “C:\>dir.” They had to know some programming, which made PCs intimidating. But over time, the PC evolved and became easier to use.

ABB’s dual-arm YuMi collaborative robot is capable of precise movements, making it attractive to industries such as communications and electronics. Image courtesy of ABB.

“I don’t even think they sell [PCs] with instruction guides anymore,” Ostby said. “Computing devices, whether a tablet or phone or whatever, don’t come with a thick manual. It’s all intuitive now.”

That’s the way robots are heading, he said. “People become used to the technology, and the technology itself becomes easier to use, as the PC and the smartphone did. Job shops will understand and make use of the technology’s benefits.”

Need for Flexibility

Suppliers are taking a second look at automation because, in many cases, their customers’ expectations have changed. Product life cycles have become shorter, production quantities fluctuate and there’s a higher degree of variation in part families. Suppliers also face increasingly stringent quality demands and a shortage of experienced, educated workers. In response, automation has evolved to do more with relatively simple controls, often while taking up less space.

As customers demand more individualized products, there is an increasing need for more flexible automation in future factories.

Collaborative robots, or cobots—such as the new, single-arm version of ABB’s YuMi—are light enough to be easily redeployed around a factory and can be mounted on tables, floors, walls or even from the ceiling, Nerseth said. “This makes it easy for manufacturers to flexibly add collaborative applications to existing lines while keeping workers

inherently safe.”

Ostby added that cobots—such as the FANUC CR-35iA, which can carry 77 lbs. (35 kg)—are affecting small and big shops. “They’re easy to set up and easy to program by lead-through teaching or traditional teaching. After the robot has been doing a job for, say, a week, you can easily teach it to do another task the next week, if necessary. The human worker can interact with it, or at least be in the operator space adjacent to it.”

SW automation minimizes the amount of valuable floor space it takes up, according to Campbell. “Automation—robots and fencing and whatever else—usually goes in front of a machine. This placement can make it really hard for the operator to get to the machine if it goes down for some reason.”

SW North America instead employs an overhead gantry design to hold its automation equipment. “It meets all the OSHA standards,” Campbell said. “If the machine or the automation itself goes down for any reason, you can go right up to the machine and access it without being encumbered by gates or the automation itself. The gantry design keeps the machine completely accessible.”

Capabilities Increase

The tasks an automation system can perform and how easily it can perform them are evolving.

“Automation used to be fairly primitive,” Campbell said. “You’d put a robot in front of a machine and trust it for very straightforward loading and unloading jobs, but no more than that.”

Campbell added that automation is at a new level. It rotates, stacks and deburrs parts and puts in different A and B loads. “All of these tasks used to take a lot of time for an operator to do. Anytime that spindle isn’t turning, you aren’t making money.”

SW’s BA 622 system features a 7-axis robotic gantry for fully automated assembly, including automatic blank part recognition via camera technology. Image courtesy of SW North America.

Improving dexterity is a feature also cited by Nerseth, who said the robotics industry has been moving in recent years toward developing systems able to handle smaller and lighter items with greater precision. “For example,” he said, “a YuMi collaborative robot can tirelessly work with needle-threading precision the entire day. This ability is critical for tasks such as manufacturing mobile phones, which have many small parts to assemble, machine tending and inspection applications.”

It’s not only the automation that’s improving but the technologies that integrate with it, such as vision and force control and safety, Ostby said. Such technologies reduce the cost of automation, enabling small job shops to come on board.

He used vision as an example. “If a robot is finding a part with a vision system, it can change from one part to the next very easily. In the past, getting parts positioned accurately so the robot could find them was a time-consuming challenge. It’s becoming less of an issue with vision guidance.” FANUC America used to equip 10 percent of robots with vision. Now, according to Ostby, it’s 67 percent.

Enhancing the Workforce

Campbell, Ostby and Nerseth all stress the ease of using modern automation—how simple it has become to set up, program and run. The impetus for this has been the much-discussed skills gap challenge: As baby boomers retire, there are simply fewer well-trained, educated people in the manufacturing workforce. Automation needs to be able to be guided by less-skilled hands.

There is a lingering suspicion—at least in the Greater Detroit area—that the real purpose of automation is simply to replace flesh-and-blood workers. All three men vehemently disagree with this characterization. It’s simplistic, especially given the shortage of qualified workers.

Everyone is trying to find qualified people, Campbell pointed out. “It’s amazing how things can change in 10 years. First you couldn’t find a job operating a machine, and now you can’t find anybody to operate a machine.” He added that for shops that have a product to make but can’t find qualified people, automation is an effective way to get some jobs completed while maximizing the value of the people they do find.

An important benefit of cobots is their ability to help offset shortages of skilled labor, which is a global issue. “Japan, for example, has nearly one worker in five within a decade of retirement,” Nerseth said. “Many countries face similar demographic time bombs. There is little relief in the pipeline, as today’s knowledge-based workers want rewarding mental challenges, not physical challenges or dull, repetitive tasks.”

It’s becoming more efficient for robots to do such repetitive work than was possible in the past. “The new robots are having the long-term effect of channeling people into more creative and fulfilling activities,” Nerseth said.

For years, FANUC has been actively waging a campaign called “Save Your Factory.” Ostby explained that the point is that if a business is not competitive, it—along with all of its jobs—will disappear. The challenge is not limited to the factory floor, Ostby said. In today’s competitive environment, “in every area of business, from HR to finance to product development, you need to make yourself more competitive, more effective and more efficient. When you do that, you grow your business and actually create jobs in the areas that add value.”

Factories that automate boring, low-paying jobs with high turnover not only stay competitive but can elevate workers to more interesting, better-paying jobs.

“It goes back to agriculture,” Ostby noted. Automating tedious, repetitive factory activities is comparable to “what the farm tractor did to field workers, what the cotton gin did to all the people who used to have to pick the seeds out of the cotton by hand. It’s been a fact of life since the early 1800s. Automation is going to continue.”

Contact Details

Related Glossary Terms

- Rockwell hardness number ( HR)

Rockwell hardness number ( HR)

Number derived from the net increase in the depth of impression as the load on the indenter is increased from a fixed minor load to a major load and then returned to the minor load. The Rockwell hardness number is always quoted with a scale symbol representing the indenter, load and dial used. Rockwell A scale is used in connection with carbide cutting tools. Rockwell B and C scales are used in connection with workpiece materials.

- boring

boring

Enlarging a hole that already has been drilled or cored. Generally, it is an operation of truing the previously drilled hole with a single-point, lathe-type tool. Boring is essentially internal turning, in that usually a single-point cutting tool forms the internal shape. Some tools are available with two cutting edges to balance cutting forces.

- centers

centers

Cone-shaped pins that support a workpiece by one or two ends during machining. The centers fit into holes drilled in the workpiece ends. Centers that turn with the workpiece are called “live” centers; those that do not are called “dead” centers.

- relief

relief

Space provided behind the cutting edges to prevent rubbing. Sometimes called primary relief. Secondary relief provides additional space behind primary relief. Relief on end teeth is axial relief; relief on side teeth is peripheral relief.

- robotics

robotics

Discipline involving self-actuating and self-operating devices. Robots frequently imitate human capabilities, including the ability to manipulate physical objects while evaluating and reacting appropriately to various stimuli. See industrial robot; robot.

- turning

turning

Workpiece is held in a chuck, mounted on a face plate or secured between centers and rotated while a cutting tool, normally a single-point tool, is fed into it along its periphery or across its end or face. Takes the form of straight turning (cutting along the periphery of the workpiece); taper turning (creating a taper); step turning (turning different-size diameters on the same work); chamfering (beveling an edge or shoulder); facing (cutting on an end); turning threads (usually external but can be internal); roughing (high-volume metal removal); and finishing (final light cuts). Performed on lathes, turning centers, chucking machines, automatic screw machines and similar machines.

- vision system

vision system

System in which information is extracted from visual sensors to allow machines to react to changes in the manufacturing process.

Contributors

ABB Inc.

(800) 435-7365

www.abb.us/robotics

FANUC America Corp.

(888) 326-8287

www.fanucamerica.com

SW North America Inc.

(248) 250-4154

www.sw-machines.com