As economic outlooks go, 2018 is looking up

As economic outlooks go, 2018 is looking up

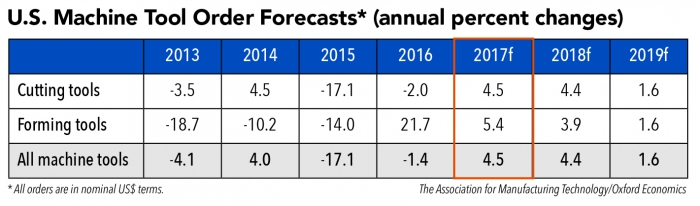

As 2017 winds down, economists and experts agree that manufacturing has had a good year and growth should continue throughout 2018 in the U.S. and globally.

As 2017 winds down, economists and experts agree that manufacturing has had a good year and growth should continue throughout 2018 in the U.S. and globally.

With a few exceptions, the world's economies show more collective momentum than at any time since the mid-20th century, said Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics Ltd., Oxford, U.K. He said global growth, domestic resilience in spending and a weakening dollar all bode well for the immediate future.

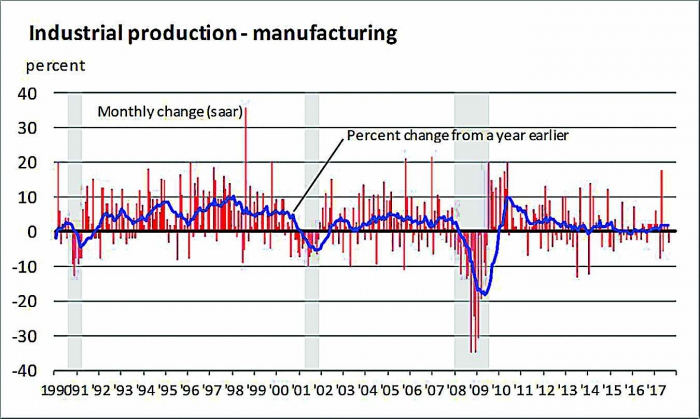

"We can clearly say that manufacturing is showing one of its better years compared with the last couple of years," said William Strauss, senior economist and economic adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. He said the weakening dollar has made U.S. goods less expensive for foreign customers and made foreign goods more expensive to domestic customers. "Since the early part of this year," he said, "we saw the dollar peak, but it has come down. That has certainly taken the pressure off and, relatively speaking, made the U.S. a better bargain, and that is part of why we've seen this bounce back."

There has been renewed optimism among manufacturers and other businesses, Strauss said, citing the stock market's performance and public opinion polls conducted after the presidential election.

Daco agreed, saying the confidence, as well as strong orders and backlogs, indicate increased activity for 2018—"perhaps even somewhat stronger activity than we had this year." He said if foreign or domestic demand or confidence wanes, however, manufacturers may slow output, reducing growth.

"The main thing that people have to pay attention to is what's going on in D.C. to see whether we get any kind of stimulus from the administration or Congress," Daco said.

Strauss said U.S. markets generally look fine and are not at all "overheated," so the main risks are from outside the country—for example, issues with the Middle East or North Korea. That said, the ever-present risk of poor monetary or fiscal policies at home or effects from changes in taxes, health care, trade or immigration could hurt manufacturing. Absent a setback, he believes that 2018's investment cycle will rebound for the first time in years because of higher employment and rising labor costs.

He thinks many firms will try to put money toward capitalizing their businesses. "An investment tends to be a greater risk than hiring people," Strauss said. "If you happen to get into a recession in the future, it's much easier to remove workers to shed costs, whereas it's more difficult to leave a machine sitting idle to remove costs." But avoiding capitalization of manufacturers' businesses is becoming more difficult given where the business cycle is, he noted.

An unexpected economic factor in 2017, which could continue to affect 2018, was the recurring hurricanes that made landfall in late summer. They are causing an "upsy-downsy or downsy-upsy" in production to repair and replace damaged and destroyed property, Strauss said. "The old adage is: Natural disasters are good for GDP," he said. "That is kind of the reality."

Market Trends

Daco said the energy sector remained relatively stable in the storms' aftermath.

Craig Pirrong, professor of finance and director of the Gutierrez Energy Management Institute at C.T. Bauer College of Business for the University of Houston, said oil prices increased in the wake of the hurricanes.

"The market has tightened," he said. "Based on historical experience, we would expect an increase in energy investment until about spring. Going much beyond that, I would be reluctant to speculate."

Pirrong said the energy sector has continued to grow in the U.S. since OPEC's recent cuts in oil production. Like many other economic observers, he considers the potential implications of the Trump administration. In the case of energy, he does not anticipate federal restrictions on the market.

"There aren't going to be regulatory or political constraints on investments in the energy sector that there might have been under a Clinton administration," Pirrong said.

There are political and regulatory concerns about other markets, though, such as automotive. Federal regulations and politics could have a "dramatic impact" on that industry, said Charles Chesbrough, senior economist and senior director of industry insights at Cox Automotive Inc., Atlanta. He cited renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, pressure on imports and tariffs as examples.

"There's a tremendous amount of volatility and variance in this administration in terms of policy," he said. "So it's very hard to say in advance."

Compared with other sectors, the automotive industry performed strongest after the Great Recession, Strauss said, and it still has a good outlook.

Chesbrough said job creation remains robust, consumer confidence is strong and interest rates are relatively low. "That is the trifecta for the automotive market. People are employed, people are confident and people are able to borrow money."

Despite unpredictability in Washington and evolving market factors of supply and demand, he said the automotive sector should stay strong next year. He also cited the hurricanes as a "net positive" for automotive and said if a downturn does occur unexpectedly, the industry is in a better place to adjust than it was a decade ago. Instead of factories closing, it would be more likely to see shifts curtailed.

Risks to Manufacturing

Long-term risks loom on the horizon—risks for all of manufacturing. Many relate to technology, such as industrial robotics, artificial intelligence and 3D printing. Each of those has the capacity to transform industry, said Darrell West, vice president of governance studies and director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution.

"Robots are rapidly getting integrated into factories," he said. "There even are manufacturing plants in China that are fully automated, with only a handful of humans to oversee the robots. This is boosting productivity and saving time during production. Artificial intelligence is helping manufacturers optimize resource utilization and energy management. 3D printing is expanding the scope of production into new realms and making it possible to manufacture items at a distance."

Manufacturing output is starting to increase after being unchanged for the past couple of years. Image courtesy of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

But the biggest challenge at the moment is cybersecurity, he said.

"There are many unwanted incursions as hackers and state-sponsored intruders seek insight into manufacturing processes," West said. "It is easier for them to steal than create their own products. This is a big problem for U.S. manufacturers in particular."

Risks aside, there is much for manufacturers to feel positive about in the next year. Daco said even if global growth fails to accelerate, manufacturers should keep in mind that the relative pace of growth and absolute pace of growth are different things. While accelerating growth is always a goal, steady growth may suffice.

"We're seeing momentum," he said, "something that we really hadn't seen in the past 2 years. It may be sustainable."

After witnessing the U.S. economy's steady 2 percent growth mode for several years, Daco said, "I'll take 2 percent growth any day over 3 percent or 4 percent growth that's unsustainable."

Chesbrough said it is difficult not to feel good about manufacturing overall, especially considering that there are no obvious economic bubbles that could be viewed as immediate threats.

"It's hard to point to anything right now that has the potential to derail the economy," he said, adding that something unforeseen never can be ruled out, such as interest rates being raised too high and too quickly, the nation's debt ceiling not being increased or the federal budget not being passed. "But in general, just looking at the economy as a whole, it's still looking quite strong. And that should remain the case throughout 2018."