The majority of engineers I’ve worked with are solution seekers who usually go out of their way to make things easier for people working on their projects.

However, as a result of the physical separation of engineering departments from machine shops, communication and feedback often suffer. Machinists who provide feedback to engineers help both groups work together more productively, and engineers would do well to spend time talking with shop personnel to determine what obstacles they face. Experienced machinists generally have good mechanical aptitude, are in tune with reality and have, unfortunately, worked on projects that didn’t go so well.

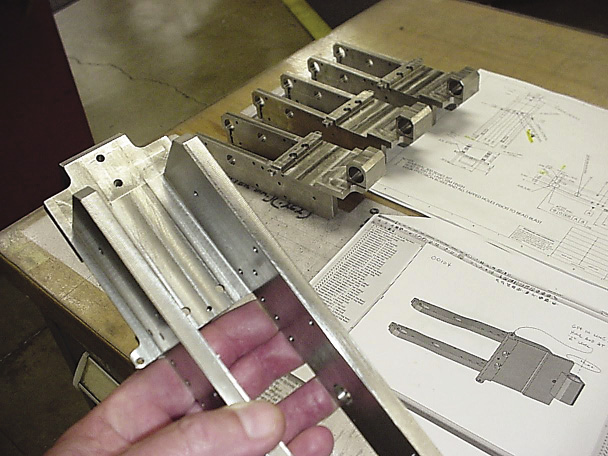

For shop personnel, the best information an engineer can provide is both a CAD model and detailed drawing with tolerances. Second best is a detailed drawing, but that forces a machinist or programmer to construct a computer model, promoting a greater likelihood of errors. Providing only a computer model is sometimes sufficient, but it leaves tolerances open to interpretation. All images courtesy J.Harvey.

If engineers bounce ideas off of machinists as they design their projects, especially if they are unsure about something, engineers will likely be ahead of the game. The following are some tips for engineers to enhance their interaction with shop personnel.

- Catch mistakes at the computer. Computers have been a blessing in manufacturing, because good designers have a tool that helps them design efficiently; they’re also a curse, because careless designers have the same tool.

“Computer people” are accustomed to having things happen instantaneously. What some overlook is that the same spontaneity does not exist in manufacturing. Something as simple as a hole being in the wrong location can be a setback. Engineering and executing fixes are often expensive, stressful and time-consuming. The best time to catch mistakes is at the computer, not when parts are being machined or

assembled.

- Pay attention to details in your designs and drawings, and when you are working with shop personnel. Machinists often don’t know the function of a part and rely on a drawing to choose the tools and methods to machine parts. Getting accurate and clearly defined drawings to the shop floor is an engineer’s job. The devil, as they say, is in the details.

- Submit both a CAD model and detailed drawings to shop personnel. Submitting only a CAD model can save time, but at the expense of leaving tolerance interpretation open to the machinist or programmer. Experienced machinists can generally tell from a CAD model what dimensions are important—but not always. For example, a machinist wouldn’t know the difference between precisely located dowel pin holes and drilled holes just from a model.

- Avoid initiating a poorly planned project for machining and fabricating just to get a project moving. New projects have enough unpredictability built into them already; if you’ve been in manufacturing for any length of time, you’ve probably been involved with projects that fought you from the moment of conception to the day they died.

Getting off to a good start is critical to getting the upper hand on a project and keeping it on track. When machinists take over, it is equally important that they get off to a good start with thoughtful planning and execution.

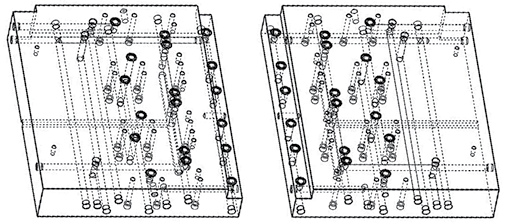

Mirror images of parts made from one drawing are often needed, but avoid cramming too much information into one drawing. Mirror images, by design, always open like a book.

- Avoid cramming too much information into one drawing. I often see drawings where a mirror image of the same is called for. Generally, that doesn’t cause confusion. However, when mirror images are called for with exceptions, things can go south in a hurry.

An example of this confusion happened with a blow-mold project. The right- and left-hand molds and mold bases were mirror images, but the cooling lines for the front half and back half of the mold bases were a little different, as were the mounting holes on the front half and back half. This was all described in one drawing.

When the mold bases returned from the vendor, they looked like Swiss cheese and couldn’t be saved. I begged the engineer to make four separate drawings on the next attempt, one for each mold base. He did, eventually. We now have four good mold bases, albeit 2 months late and about $20,000 over budget. Paper is cheap. Use it to avoid confusion.

Related Glossary Terms

- computer-aided design ( CAD)

computer-aided design ( CAD)

Product-design functions performed with the help of computers and special software.

- tolerance

tolerance

Minimum and maximum amount a workpiece dimension is allowed to vary from a set standard and still be acceptable.

ARTICLES

ARTICLES